- Home

- Gail Carriger

Funny Fantasy Page 11

Funny Fantasy Read online

Page 11

There was a person here. Sitting behind a desk. There was nothing on the desk except a thin black vase with three white lilies sticking out of it. The person behind the desk was indeterminate, dressed in something that could have been white, or maybe gray, but wasn't quite enough of either.

"Please sit down. Be comfortable."

"Sit where?" I looked behind me. There was a chair there. Now. I sat. It was neither hard nor soft. Neither comfortable nor un-.

"Excuse me?" I said.

"Yes?"

"Is it necessary for this whole place to be so … so indeterminate?"

"Mm, yes. I see your point. Just a moment. Is this better?" The space was now identifiably a room. Bare blank walls. No door.

"Um, no. It isn't."

"Something wrong?"

"It's—it's very stark. Institutional. Not very comfortable."

"You think this place should be comfortable?"

"Is there any reason why it shouldn't be? And you did tell me to be comfortable."

"Point taken. How's this?"

I looked around. Now the space was defined by Grecian pillars that stretched infinitely upward. Long silky-white drapes wafted in a soft breeze. Beyond, summer-blue sky with soft cumulus pillows here and there. "Nice," I admitted. "A little bit of a cliché, very Warner Brothers, but—"

"I can change it, if you wish—"

"No, no thanks. This will do."

"You're sure."

"Quite."

"Can I get you something? Water? A soft drink? Iced tea?"

"No, I'm fine. Really."

"Good."

I waited. He waited. We waited. He still seemed indeterminate.

Finally, I asked, "Are you God?"

"I'm an aspect of the universe."

"You don't look like an aspect."

"Oh? How do you think an aspect should look?"

"I don't know. Like God, I guess."

"And what does God look like?"

I shrugged. "Like God. Unmistakeable."

"I see. Do you prefer the George Burns or the Morgan Freeman iteration? Or perhaps something more in the Charlton Heston or Michelangelo mold? Or maybe Hattie McDaniel?"

"Hattie McDaniel?"

"A very popular aspect."

"Um, no. I just—"

"How's this?" Gregory Peck. The Atticus Finch version. "Will this do?"

"Yes. That's fine."

Gregory Peck looked at me across the desk. "Is there anything else?"

"Is this where I get judged?"

"No."

"I get judged somewhere else?"

"No."

"Well, where do I get judged—?"

"Being judged is important to you?"

"No. Yes. I mean, I thought it was part of the deal."

"No, it isn't."

"No judgment at all?"

"No. Are you disappointed?"

"Well, sort of. I thought I did pretty good. Didn't I?"

"I don't know. Why don't you tell me—"

That stopped me for a moment. "I have to tell you?"

"It's a start."

"Oh, I see. This is all self-service. Like a cafeteria. I'm supposed to sort it out for myself, argue both sides of the case, all my good works versus all my sins, right? I get to undertake a self-examination of my entire life, however long as it takes, and then finally pronounce my own judgment. Right?"

"No," said Gregory Peck.

"No…?"

"No."

We waited some more. He waited while I sorted it out in my head. No judgment. But if there's no judgment, then what is this place? What am I doing here?

"Is this Heaven? Or Hell?"

"What do you want it to be?"

"Look, you're the aspect. You're the one who knows what's going on. Not me. So could we just get on with it?"

"We are getting on with it. This is it."

"This is it? This is it? This is it?"

"Yes."

"What about eternal reward? Eternal punishment? Judgment day? Heaven? Hell? God? St. Peter? Pearly Gates? Satan? Fiery pits of agonizing brimstone? Demons? Pitchforks? Are you telling me none of that is here? If it's not here, where is it?"

"Is that what you want?"

"No, I don't—"

"What is it you want?"

"I want an explanation. I think I deserve an explanation, don't you?"

"What I think is irrelevant. This is your space."

"Did I end up in some kind of purgatory? Limbo? Is that it? This is a waiting place, isn't it? How long do I have to wait? Ten thousand years? A million? That really doesn't seem fair. I only had 72 years on Earth. Why should all of eternity be determined by a mere flick of time? I didn't even have enough time to—to live a whole life, to learn enough to—to be wise. I didn't have enough time to do all the things I planned to do."

"You had 72 years, 4 months, 3 days, 22 hours, 14 minutes, 33 seconds. Wasn't that enough?"

"No, it wasn't."

"It was a lot more than most people get. And you had your health."

"Fat lot of good that does me here."

We waited some more.

"So okay, fine. I get it. What happens next?"

"Nothing."

"Nothing?"

"That's right."

I inhaled. I exhaled. Mostly for effect. That was interesting. I could breathe here. I did it again. "Nothing," I repeated.

"That's right," said Gregory Peck. "Is there something you would like to have happen?"

"Can I ask you something?"

"Ask anything you want."

"Will you answer honestly?"

"Of course."

"How long does this go on?"

"As long as you want."

"Where is God?"

"God is here."

"Here?"

"Yes."

"Where?"

"Here."

"Do I get to meet God?"

"If you wish."

"When?"

"Whenever you wish."

"How about now?" I said.

"All right."

Nothing happened.

I looked across at Gregory Peck. He did not seem antagonistic. In fact, he seemed very nice. He wasn't doing this deliberately.

"So, where is God?"

"God is here."

"Are you God?"

"I'm an aspect."

"Yeah. I got that part. So, let's see. There's no Heaven. There's no Hell. There's no Day of Judgment. There's no reward, no punishment."

"Do you want any of those things?"

"No, I don't." I got up from the chair, went to the edge of the room—the space—and stared out into the eternal blue. I scratched behind my ear.

"Is it this way for everybody?" I asked.

Behind me, the aspect answered. "No. It's this way for you."

"Hm." Well, that was useful. The afterlife was a personal experience. A puzzle that each person had to solve for himself. "So how much time do I have here?"

"As much as you want. We create it as we need it."

"Yes, of course. I should have known. Thank you."

"You're welcome. Are you sure I can't get you anything? Water? A soft drink? Iced tea?"

Something went click. Or klunk. Or whatever sound a small epiphany makes inside your head—if you have a head.

But I was starting to figure it out. I walked back to the chair and sat down at the desk. The aspect sat across from me. He waited patiently.

"You work for me, don't you?"

"Yes, I do."

"You didn't tell me that."

"You didn't want me to. You wanted to see how long it would take for you to figure it out for yourself."

"Well, this is embarrassing."

"Every time."

"Right." I scratched behind my ear again. An interesting sensation. I'd have to remember that one.

"I like playing jokes on myself, don't I?"

"Yes, sir, you do. Who else do you have to play jokes on?"

> "Yes, there is that."

"That was a good one with the redhead, though. Nicely orchestrated."

"Yes and no. It didn't seem like fun from the inside."

"I guess not."

"I'll have a cappuccino, please."

"Right away—"

And there it was. Coffee was one of my better ideas. Almost as good as sex. I put the mug back down on the desk. "So," I said. "I guess I'm ready for the next life."

"Very good, sir. What would you like to try this time?"

"Well, I'm just brainstorming here, but how about this—"

This story originally appeared in Galaxy's Edge, 2015.

David Gerrold has been writing science fiction for half a century. His novels include When Harlie Was One, The Man Who Folded Himself, the Dingilliad series for young adults, and the Star Wolf series. He's currently editing book five of his seven-book War Against the Chtorr trilogy. David Gerrold has written for many different television series, including Twilight Zone, Land of the Lost, Babylon 5, Tales from the Darkside, Sliders and The Real Ghostbusters. He also wrote scripts for Star Trek Animated and Star Trek: The Original Series.

Fairy Debt

Gail Carriger

"I WON'T DO IT, I tell you!" I was mad, and I had a right to be.

Aunt Twill sighed dramatically and swished about where she sat in the lake shallows. Aunt Twill did most things dramatically. She was the naiad of the Woodle River, and it was a bit of a dramatic river, full of small but excitable waterfalls.

"Unfortunately it's your debt to pay."

I crossed my arms and glared at her.

She explained as though to a child, "Your mother was rescued from certain death by a human King. That's a great debt of honor for a fairy to endure."

"Yes, but these things are easily taken care of," I insisted. "All mamma had to do was show up at the christening of the King's firstborn and grant it something humans care about." I tried to come up with examples. "You know—beauty, boxing, bee keeping. That sort of thing."

My aunt fluttered her webbed fingers about her face in exasperation. "Yes, but your mother missed the christening and, most inconveniently, died."

I sighed. I was only a nestling when she died, so I didn't remember. They say it had to do with a golden barbell and a frog with a steroid addiction but it was all kept very hush-hush.

Aunt Twill reached down and gathered a few water lilies about her. "So the princess has no fairy godmother and you can't grow wings." She began braiding the lilies into a chain with her magic. "An honor debt warps wings. Especially in the young."

I fluttered my four stubby wings angrily in reply. They weren't any use to me, but I liked to flap them for effect.

"Debts carry forward to the next generation." My aunt draped the water lilies about her neck. "You owe the princess."

"But I've no working magic without working wings. Nothing to pay her with."

"You have your Child Wishes."

I snorted. A fairy's Child Wishes had power over only one thing, usually to do with human domestic life. Evolutionarily speaking, this ensured that mankind would always find value in sheltering fairy offspring. My cousin, Effernshimerlon, could manufacture safety pins as needed. My Wishes improved baked goods. For a fairy potluck I once made banana puff cupcakes so delicious they caused a visiting earth dragon to cry. Earth dragons are fond of cupcakes. They have notorious (and very large pointy) sweet-tooths.

"What could I do with my Wishes?" I asked Aunt Twill. "Ensure that the castle's bread rises perfectly for the next one hundred years?"

I was being facetious, but my aunt took me seriously. She bobbed about in the lake and the lily chain fell from her neck.

"No, I don't think that's enough. Not unless the castle's bread is cursed."

I raised my eyebrows at her. "What do you suggest, then? I can't be fairy godmother to the princess, she's my age, that'd be ridiculous." I felt as though everywhere I looked there was a troll with a club pointed at me, and no troll-pacifying porridge in sight. Was there no way to pay off mother's debt? "What do I do?"

Aunt Twill shut her damp old eyes. I could practically hear her thoughts sliding about in her head, like water over pebbles. Very slow water over very large pebbles.

"You'll have to pay it back the hard way."

"Oh and what's that?"

"Old-fashioned servitude."

I PACKED UP and trekked west, away from the Woodle River, toward the Small Principality of Smickled-on-Twee. There lived a king who'd once rescued my mother from certain death.

What else was I to do? I wanted wings. What good is a fairy without wings?

I'm tall for a fairy (all that naiad blood) but really very short for a human. I come up to the knees of the average adult male. With stunted wings tucked under a tunic I looked like a hunchback. There's only one role at a royal court for a short hunchback: jester.

I knew it would all end in tears the moment I saw the hat.

"Do I have to wear it?" I asked the Most Jester in shock, staring at the ghastly thing.

He jiggled his own at me. A four-pronged confection of red, blue, and green plaid tipped with silver bells. "Required uniform, I'm afraid," he replied. Clearly he'd gone into the profession out of physical necessity as well. He was extremely tall and decidedly skinny with a great beaked nose and a very deep voice.

His hat was elegant compared to the one presented to me. Mine had only three prongs and was worn so that one prong always fell directly in front of the eyes. One of the prongs was yellow with pink spots and the other two were purple with white stripes. Mankind may have made uglier hats but I doubt it. Don't even get me started on the subject of the bells. The darn thing was covered in them.

I put it on, and the accompanying checked green pumpkin pants and doublet (which, next to the hat, seemed quite somber), and slouched after the Most Jester toward the Throne Room.

"Your Majesty," the Most Jester bowed low to the king. Too low, for he toppled forward, stumbled and sprawled flat on the floor. The assembled courtiers laughed appreciatively. "May I introduce our new Least Jester?" He waved a spade-like hand in my direction from his prone position.

I had fairy grace at my disposal even if I didn't have working wings. So I did a flip and two somersaults to end in a bow at the king's feet.

The king nodded at me happily, and the princess clapped. Not every court was lucky enough to have a tumbling jester.

"Why," said the princess, looking at me closely, "you can't be much older than me."

I looked up at the human who held my fate in her hands. She didn't seem all that bad—a little chubby for a princess and rather graceless. Hadn't she been given any fairy gifts at all? I know my mother fell down on the job, as it were, but this poor thing was practically ordinary! She seemed to know it, too. She slid off her throne in the most humble manner, and bent down in order to properly introduce herself to me.

"Princess Anastasia Clementina Lanagoob. How do you do?"

I came out of my bow. Standing upright my head ended just below her waist. I reached up and shook her pudgy hand with my tiny one. "Bella Fugglecups," I replied. I couldn't give her my fairy name, of course, too recognizable. Aunt Twill had invented this one as an alternative. It was silly, but so was my hat.

"I shall call you Cups," announced the princess.

"Only if I can call you Goob," I retorted.

The king seemed appalled by this impertinence, but the princess was clearly delighted. The statement made her laugh. Which is, after all, a jester's job.

"Done," she said, letting go of my hand. "Will you teach me how to tumble?"

I looked dubiously at her full white skirts covered in gold beads and silver embroidery.

"Now? If you insist, but I hope your under-things are as attractive as your outer ones."

The princess laughed again. The rest of the court gasped in shock. The Most Jester made a frantic sawing motion across his neck. I had no idea what he was on about.

&nbs

p; "Anastasia Clementina, I forbid such an undertaking!" The king rose from his throne and glowered down at the two of us. He was a large sort of human, full of hair, and prone to some kind of disease that made his face go all red and splotchy. It was doing so now.

"Please, Daddy," the princess turned big muddy brown eyes on her father. Cow eyes. "I'll change my outfit."

The king sighed.

What I didn't know then was that the princess rarely took an interest in, or asked for, anything. When she did, her requests carried more power. It's a good approach to life, generally gets one what one wants. (So long as one doesn't "want" too often.) I would come to appreciate this character trait over the course of my association with Princess Goob, for all too often we fairies are on the receiving end of demanding humans. Take Cinderella for example—with her gown, and her coach, and her glass slippers, and on and on. I mean, really! But, I digress.

"Very well." The king ceded defeat. He looked at me. "You don't mind?"

I tilted my head way back. "It is my honor to serve, Your Majesty." What else could I have said?

I did a back bend, kicked my heels up, and walked away from the two royals on my hands until I'd rejoined the Most Jester. Then I flipped to standing.

The princess clapped delightedly.

I bowed to them both.

"Tomorrow at noon, Cups," she ordered.

"Noon, Princess Goob." I agreed, and followed the Most Jester out of the audience chamber.

"DO YOU THINK it's enough of a service?" I asked Aunt Twill that evening through a small cup of tea.

Her image wiggled in the brown liquid. Normally tea talking is a delicate spell requiring both parties use bone china, Earl Grey, and silver stirring spoons. But Aunt Twill had a contract with the tea daemons that allowed her conversational access (between the afternoon hours of half-past three and five o'clock, of course) to any cup in the kingdom. It's a naiad gossip thing.

My aunt extracted a small gudgeon fish from her hair and ruminated. "I doubt teaching a princess acrobatics constitutes proper repayment of an honor debt. Though it is a nice thing to do. Why would she want to learn, do you think? It certainly isn't normal princess-y behavior."

I shrugged. "She isn't a normal princess. More like a normal dairymaid. Poor thing."

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

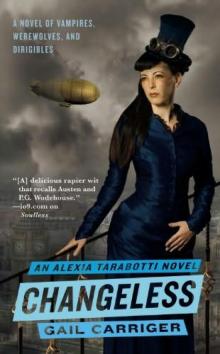

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

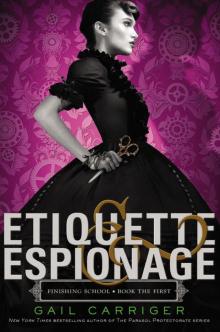

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

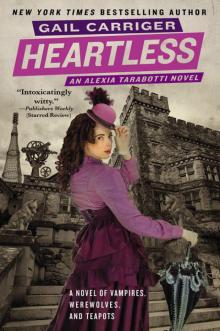

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

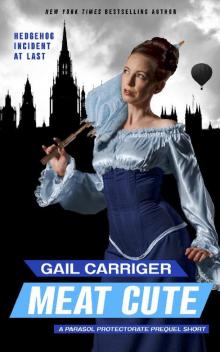

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3