- Home

- Gail Carriger

Waistcoats & Weaponry Page 13

Waistcoats & Weaponry Read online

Page 13

Sophronia selected the very last of the three doors.

She looped Bumbersnoot’s reticule strap over her neck and went first, without discussion. Carefully, holding fast to the roof railings, she eased over the edge and lowered herself down. She was tall enough so that when her arms were fully extended, she only had a short drop. It was tricky, as the footboard wasn’t very wide. She wobbled dangerously on the landing and nearly tumbled off the train entirely. Sidheag and Soap, who were tall, would have an easier time of it, but she’d have to watch Felix and Dimity carefully. She peeked in the small window of the coach door. Inside, it was dark and apparently vacant. She motioned for the others to wait while she fished her picks out of a pocket and jimmied the lock. The tumblers went over without protest. She scooted along the footboard, out of the way, and the door opened easily.

It was eerie inside. Moonlight filtered in from the windows opposite the door, slanting across the two facing blue velvet benches and dust motes in the air. The compartment was definitely empty, and she would lay good money on the other two being vacant as well. This entire first-class carriage seemed deserted. The coach held no luggage and no evidence that occupation was ever intended. It was odd, like a ghost train.

Sophronia, thinking of her exhausted friends, made a quick decision. It was unlikely anyone else could climb down as they had, so they should be safe until they reached a station. Climbing back to the roof and down to the next-over footboard seemed like an excess of precautions when this coach was safe and empty, and she was exhausted. She put Bumbersnoot down on the floor to snuffle about in the dark. If he came across anything unusual, he’d swallow it either to burn in his boiler or to be kept in storage. Which reminded her of the present delivered by Mrs. Barnaclegoose. There came a clattering behind her, and she forgot once more.

Soap swung down and in. With the door open, the narrowness of the footboard was not such a challenge. One could simply dismount by falling forward into the coach. Which was what he did.

“Ah, good, you managed it,” greeted Sophronia.

Soap gave her a dour look.

“I know, stuck with all us girls, must be tragic for you.”

The others began leaning over from the roof and passing or throwing down the supplies, with Sidheag and Dimity, trained in stealth, trying their best to keep Felix muffled. There could, of course, be occupants in the other carriages, but they were either heavy sleepers or the sound of the train covered any noises made by the five new passengers in first class. Six if you counted Bumbersnoot.

They crammed inside the coach. As Soap had feared, it was a mite intimate for society standards. Sophronia closed and bolted the door, drawing the curtains over both it and the windows opposite in just such a way that she could peek out a corner if needed. From the outside the drapes would appear messy enough to have unintentionally rattled loose, to the untrained eye.

The five sat down and looked at one another in profound relief. The three girls took the forward-facing bench. The two boys sat opposite. This seating arrangement ensured a respectable distance between them, one that even Mrs. Temminnick might approve. First-class coaches were luxurious. Although, after falling on top of one another in an airdinghy recently, such concerns seemed silly. And Soap still looked uncomfortable with the arrangement.

Save Sidheag, they were all still wearing masquerade outfits, without masks, hair sticking up or fallen loose.

“We must look a treat,” said Dimity into the exhausted silence.

Sophronia shook herself. “You’re right, we should change. Best if we look more like stowaways, in case we do get caught.”

The boys rose and made as if to leave the coach.

Sophronia had no idea where they intended to go, perhaps outside to balance on the footboard or climb back onto the roof? She shook her head. “We should stick together. We’ll have to trust you two to turn around and not look.”

Dimity went white as a sheet, more terrified by this than the hair-raising ride they had recently endured. “Must we? If anyone finds out, our reputations will be in absolute tatters, so…”

“We must ensure no one finds out,” said Sidheag, already unbuttoning her hideous tweed dress.

Then Soap, still facing them, went red as a beet at Sidheag’s action and hastily turned to face the back of his seat, eyes screwed tightly shut.

Felix, after one startled glance, did the same. He did not look quite so embarrassed.

Sidheag continued with her changing while Sophronia upended the bag of clothes. She rummaged through for something that looked to fit her friend, realizing that they’d have to cannibalize the train curtain cords for belts. Dimity helped Sidheag remove her corset, tight lipped with disapproval. Sophronia envied her the fact that she didn’t have to wrap. Sidheag donned a shirt, vest, and trousers. Her boots were already so practical as to be almost masculine. Once out of her dress, she looked very like a boy, lanky with mannish features. Were it not for her long hair, she could pass without further mussing.

“We could cut it,” said Sophronia, who already had out her sewing shears to strip a petticoat for chest wraps.

She would never have thought Sidheag vain, but the girl looked genuinely perturbed at the suggestion.

“It’s her best feature,” protested Dimity.

Sidheag said, very quietly, “Captain Niall prefers long hair.”

“Oh, does he indeed?” said Sophronia, struggling to keep a straight face. “We’ll leave it, then.”

Dimity whispered, “How did you find that out?”

Without answering, Sidheag plaited and wound her hair up tight to her head. She pulled a cap on over it and transformed, suddenly, into a rather good-looking young man. She then helped unbutton Dimity’s beautiful gold gown. Sophronia stuffed it unceremoniously into the sack, which made Dimity look as if she might start crying. She refused to remove her stays, and chose some of the baggiest of the clothing so that she looked like a strangely top-heavy vagabond. Even in plaits, Dimity’s hair was quite poufy and held her cap out about her head. In the end, she resembled nothing more than a walking, talking mushroom. With her round, feminine face, one really had to squint to see her as male.

After brief discussion, they added a smudge of mustache to her upper lip with a bit of coal from Bumbersnoot’s stores. It wasn’t much help.

Sophronia stripped self-consciously, including her stays, before pulling on a shirt and jodhpurs. She had a passing good figure, but fortunately it wasn’t overly generous. She put her masquerade apron back on, instead of a waistcoat. Over that she added a tweed hunting jacket. It made her look like a butcher’s boy with a pocket obsession, but she liked how useful the apron was and wasn’t going to let it go.

“You can turn back ’round.”

The boys did so. Felix snickered at Dimity’s appearance, but Soap was still so embarrassed he kept looking anywhere but at them.

“What’s he up to?” Felix asked, pointing to where Bumbersnoot, near the door, made a funny little circle of discomfort.

“Oh, dear,” said Dimity. “Look away, do.”

Felix did not, as there was nowhere else safe to look, watching with interest as Bumbersnoot squatted and ejected, out his back side, the gift Mrs. Barnaclegoose had passed along. It was a most undignified and anatomically accurate expulsion mechanism.

“Oh, yes,” said Sophronia, reaching for it.

A bladed fan! Far nicer than the ones they had practiced with, this one was steel, with filigree handle elements, making it lighter and more delicate looking. It had a leather sheath that was beautifully embossed, looking almost like a piece of mysteriously large and elaborate jewelry as it hung from a little strap with a tassel.

“That’s a pretty thing,” said Felix. “Gift from an admirer?”

Sophronia wasn’t going to give him any quarter. “I have a certain connection in London,” she said. Letting him think in terms of suitor rather than prospective patron.

Felix’s face went slightly sou

r. He clearly didn’t like the idea of a London rival, a man already finished with his education, based in town, with funds to spare.

Sophronia had no idea how Lord Akeldama knew she wanted one. Nor how he knew Mrs. Barnaclegoose could get it to her. The dandy vampire had more than a few tricks to go along with all those fancies. However, she was rather in love, she hated to admit. With the fan, of course, not Lord Akeldama. She tested the edge, finding it beautifully sharp, and then carefully fastened the guard and put the bladed fan away in one of her larger pockets.

“What kind of connection?” pried Felix.

“A sharp one,” answered Sophronia coyly.

“Come with me to London, Ria. I’ll buy you such pretty things.”

Soap jumped in, gruff and annoyed. “Miss Temminnick doesn’t want your kind of patronage, Pickleman’s get.”

“Did I say anything about patronage?”

Sophronia sighed. “Hush up and change, please, both of you.”

Then it was the young ladies’ turn to look away while the boys stripped. Sophronia peeked—of course she peeked!—and she wouldn’t have been surprised if the other two did as well. Sidheag, raised by werewolves, had seen men bare before, but these were boys their own age—how could she resist? Besides, Sidheag wasn’t shy. Dimity rarely had the advantage, or disadvantage, but she was terribly curious about the opposite sex. Soap, Sophronia noted, had layered on more muscle than she’d expected. Felix seemed slight, white, and lean next to the sootie. Sophronia was ashamed of herself, but that didn’t stop her from taking a great number of mental notes. She’d been well trained in how to do so. It would be a while before she and Dimity could discuss the matter, and she wanted as much detail as possible for the purposes of compared opinions.

All too soon, Soap’s dandy and Felix’s jester costumes were added to the sack. The first-class coach now looked, by all accounts, to be occupied by a gang of scruffy lads bent on postal fraud or meat pie heists.

It had been a long night and everyone was glassy eyed—particularly Sidheag, who’d undertaken an entire wolf-ride from London before their balloon excursion. They agreed to take watches. Sophronia, still excited by the hunt and accustomed to prowling about late, chose first watch. She added, quite firmly, that she would take it with Soap, to forestall any bickering. Dimity stretched out on one bench and Sidheag on the other, with Felix gallantly taking the floor in the middle, using the bag of costumes as a pillow. Bumbersnoot curled up comfortably at his feet. A fact for which the young man was no doubt grateful, as the mechanimal was an excellent foot warmer.

Soon regular breathing and soft snoring meshed with the clatter of the train.

Soap stood near the door, peeking out into the night. Sophronia, after an awkward silence, edged past Felix to look out the opposite window and see if she could guess the distance to Oxford junction. There was no clear sign of anything. Clouds had moved in, obscuring the nearly full moon. There was nothing of significance visible but damp black.

Sophronia returned to the door, standing on the other side from Soap, uncomfortable because he was uncomfortable. She examined his face, but it was closed off. Even if he wanted to talk, he didn’t want to do so here, with the possibility of three sleepers shamming and listening in. Sophronia wasn’t certain, but she thought he looked more sad than upset, and that confused her.

Casualties on all sides, she thought. I get Sidheag sorted and now Soap’s gone sentimental on me.

She tilted her head at him and tried a small smile.

His mouth twisted. He blinked slowly, looked away, and then glanced back at her.

Sophronia tried another smile.

He puffed out a short sigh, loss and resignation rolled up into it. Then he seemed to give himself a mental shake and smiled back. It was almost his old grin—only without the twinkle.

Then it was Sophronia’s turn to feel lost and forlorn. Soap had withdrawn from her, and it was her fault. Was I too tough when I yelled at him about turning claviger? It’s only that I’m worried. He should know me well enough for that. Did something happen on the journey just now? Is he still overly embarrassed about us changing? Is it Felix? Sophronia knew, at that thought, that she would lose Soap to the clavigers, if he were given half a chance. If not, he’d see her through finishing, because he was loyal, and then take off in pursuit of a pack. She wouldn’t put it past him to go for Kingair. If they managed to get Sidheag ensconced, it’d help to have Lady Kingair vouch for him.

Sophronia couldn’t have explained, if asked, how she knew Soap’s intentions so clearly. But she did. She also couldn’t have explained why it hurt so much. But it did.

They stood watch in a silence so awkward it burned the backs of Sophronia’s eyes.

TRANSMITTER ON A TRAIN

Sophronia woke Dimity with the firm shoulder grab of silence. It was a technique they’d applied before they even knew it was trained into intelligencers.

Dimity awoke quietly, automatically reaching beneath her nonexistent pillow for a weapon. It was an instinct ill suited to Dimity, like watching a duck eat custard. But sometimes Dimity was surprisingly stealthy. She would have to unlearn a great many things, if she actually ended up as a real lady.

“Your watch, my dear,” Sophronia whispered. “The sun is almost up.”

Dimity knuckled her eyes; only four hours’ sleep, but she was willing to do her duty—true friendship, that.

Soap, still at the door, stretched languidly, looking exhausted.

Sophronia went to wake Sidheag.

“Let her sleep,” said Felix’s voice from the floor. “I’ll take it. She needs the rest.”

“Very gentlemanly of you, Lord Mersey,” approved Dimity, offering him a hand up.

Felix looked at her aghast. As if he would accept aid from a lady! He wasn’t in that sorry a state, although Sophronia was sure it had been an uncomfortable night on the floor. The kohl was smudged about his eyes and his hair was sweetly rumpled. Sophronia found it most disturbing—it made him look less aloof and more approachable.

Sophronia said, “If you’re sure. You know you actually have to keep watch? Do they teach you useful things like that at Bunson’s?”

Felix gave her a dirty look. “I suspect Miss Plumleigh-Teignmott can demonstrate the particulars.”

“I intend to climb up top to watch the sun rise, check on the airdinghy, and get the lay of the land.”

Soap paused at that, before folding himself reluctantly to the floor. Sophronia had expected him to insist on accompanying her.

But it was Felix who said, “Is that wise?”

Sophronia answered, “The wise would never have left the ball in the first place. I’ll be quick, and I want to retrieve my hurlie, my wrist feels bare without it.”

Felix looked to Soap for support. “You aren’t going to stop her?”

Soap said, “Kind of you to think I could, little lordling.”

Felix glared.

Soap leaned back against the sack of costumes, head under the window, eyes heavy lidded, watching the door. He pointed at Bumbersnoot, who had moved to sit expectantly under a bench in one corner. “Can’t be too important or she’d take him with her.”

Sophronia felt a glow of pride. Soap understood her! And he trusted her. Why couldn’t Felix be more like that?

Felix, strangely, took that to heart and raised no more objections.

So with Dimity and Felix posted by the door, Sophronia creaked it open and, hugging the side of the train, inched her way out onto the footboard.

It was wet and nasty, and had she not had practice on the damp exterior of Mademoiselle Geraldine’s she certainly would have lost purchase.

Sophronia felt exposed and vulnerable. She jumped, trying to catch the top railing. She wished fervently for her hurlie as she missed and slid on the landing. She tried again, putting her will and strength into it, and managed to catch the railing and hoist herself up onto the roof. Strangely, she felt less exposed up high. As she had lear

ned during her climbing adventures about the school, people rarely looked up.

The sun rose and the clouds lifted a little. She could see, far ahead on the horizon, the tall tower of a junction box. This train, unless she was mistaken, was not expected, and no one would be manning that switch. They’d have to stop, check it, and change it over to the desired direction. She was about to witness their hosts. Would they look back at the train and see the balloon?

Sophronia crawled along the top of the carriage to the airdinghy, which was still safely strapped down. She considered knocking it off, and then decided it would make too loud a crash in the morning quiet. So she merely detached her hurlie and strapped it back in its customary place on her wrist.

She should have returned to the others at that point, but this was her first opportunity to explore without having to worry about their safety. She was dying of curiosity. What was the valuable freight in those middle cars?

She walked to the front of their carriage, jumped the coupler, and climbed across the roof of the next carriage. She moved softly and slowly, so her footsteps could not be heard by any possible passengers. She sensed that this carriage was as empty as theirs, but she didn’t know that. In front of her was the first freight carriage. From the air she’d thought it looked like a cattle cart, but up close it was a shock.

The top part of the freight carriage was, in fact, completely open to the sky. It seemed to be transporting a structure of some kind, a horse shed or similar, which boasted its own wooden roof. She suspected that there was an entrance from the front of the carriage, but in order to get there, she would have to climb across that roof, and she had no idea if it was secure or not. She risked it anyway.

Cautiously, she crawled about, examining the shed for clues. There were some funny-looking protrusions out the roof. One of them like a big metal cuspidor, another like the top part of a tuba. Eventually, she found a hatch. It was made so that something from the inside could telescope out. It didn’t seem big enough to fit a person, but she could fit her head.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

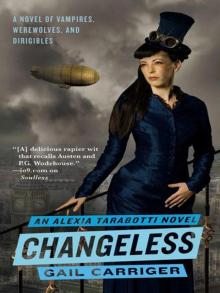

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

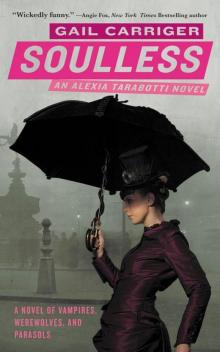

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3