- Home

- Gail Carriger

Reticence Page 13

Reticence Read online

Page 13

“I don’t know. I never tried. And how could I, if it makes immortals mortal? Now that I think on it, it does feel a little numbing, like preternatural touch.”

Arsenic let her mind wander. “I wonder if one might apply something akin to germ theory to the supernatural state. Meaning that preternaturals act upon supernaturals na unlike a medicine. That the state of undead is essentially an illness of the very air around us.”

Percy’s voice drifted down towards them from the navigation pit. “Have you read Weismann’s challenge to Lamarckism, Doctor? It’s a bit old. But we know that preternaturals breed true and mostly men, so there might be something in the blood.”

Arsenic had, of course, read the paper. She drifted away from the group at the rail and towards Percy’s pit. “The germ plasm theory of inheritance? It might apply. You’re suggesting preternatural abilities are some kind of inherited disorder, and that the capacity for excess soul is similarly transferred?”

Percy nodded. “It might not be germane, but a man named Mendel did some very interesting work with pea plants a few decades ago. Solid stuff.” He shook his head. “Never got the recognition he deserved, poor sod, but he showed that it’s possible to pass certain traits from one generation to the next, even to skip a generation in defiance of blending theory.”

Arsenic agreed. “Makes sense. Na all children are exact mixes of their parents.”

“Eye colour, for example.” Percy was looking into hers earnestly.

Arsenic settled at the edge of the pit, not wanting to intrude, but this was fascinating. “I’ve my mother’s eyes. So, if we combined these concepts with a supposition that preternatural, and therefore metanatural and associated abilities, are inherited traits that dictate certain skin-to-air reactions? Much in the manner of those allergic to wool.”

Percy’s eyes lit up. “The God-Breaker Plague means that there’s a prevalence of wool in the air and thus preternaturals react badly, because that prevalence is them, and they can’t share air with other preternaturals. Thus supernaturals react to the plague zone much as they would to preternatural touch.”

Arsenic was getting excited by this theory. So was Percy, if the light in his eyes was anything to go by. She couldn’t pinpoint exactly when they’d become chummy, probably shortly after she realized his apparent disdain was only an awkward shyness. She had started regularly leaving him pocket scones. The man loved a pocket scone. Now they were cohorts, although nothing more intimate as Arsenic hadn’t figured out how exactly to coax him past intellectual hypothesis into something less hypothetical and more, well, scientifically rigorous – so to speak. The scones didn’t seem to be sufficient.

“We always think of preternatural touch as taking the soul away from the supernatural. What if ’tis more physical? What if they dampen a supernatural’s defences, somehow?”

Percy followed her idea exactly. “Interfering with an existing skin-to-air bond?”

“Aye!”

“Is it odd how comfortable they are with each other?” Anitra wanted to know.

Arsenic looked up, only then noticing that Rue, Rodrigo, Quesnel, and Anitra were all standing around the navigation pit looking down at them.

“It’s almost like Percy has a friend,” said Quesnel.

“Oh my heavens, are you two friends?” That was Rue.

“Do they speak in English?” Rodrigo wanted to know. “That is not real English.”

At this juncture, Tasherit appeared abovedecks. It was now after sunset and evidently they were far enough away from the aetherosphere for her to be awake and moving about.

“Good evening, my lovelies,” said the werecat. “What have I missed?”

Arsenic looked up at her. “Good evening, Tasherit. May I ask, what does the God-Breaker Plague feel like to you?”

“Like preternatural touch.”

“Aye, but what does that feel like?”

“Like I’m human again.”

Arsenic frowned.

Percy said, “That’s not at all helpful, since we only know what being human feels like.”

“Perhaps we are na asking the right question.” Arsenic regarded the werecat. “What does being supernatural feel like? How is it different from before metamorphosis?”

“Doctor, that is a conversation that would take many nights.”

“Could we have it sometime?”

“Of course, but now it seems you’re leaving the ship?” She gestured to where the decklings were attempting to get Rue’s attention and let her know that the rope ladder was down and ready for embarkation.

“You willna be coming with us?”

“That close to the plague zone? No. I’ve been around it enough to last all my lifetimes, thank you. I’ll stay here on the ship like the sane supernatural creature I am.”

“Never did I think I would agree with a monster. But she speaks truth,” said Rodrigo.

“I’m coming.” Percy climbed out of his pit.

“You are?” Rue was shocked. “I mean to say, I know I ordered you to, but I didn’t think you’d listen.”

Percy was a little red. “Well, yes. I feel like it.”

Arsenic noticed he was looking at her from under his lashes.

“You feel like visiting my parents? You barely tolerate them. Percy, are you being noble?” Rue put a hand to her chest. “Protecting our new doctor from my mother?”

“Someone has to.” Percy was truculent.

“She’s that bad?” wondered Arsenic.

Rue glared at Percy. “She’s a bit much. I don’t see what Percy thinks he can possibly do to help. Most of the time, with most people, he makes everything worse.”

“Your mother likes me,” said Percy.

“My mother has horrible taste.”

Percy only changed into a visiting jacket. Virgil had been lurking and proffering it up hopefully.

“I’m grateful, for my part,” said Arsenic, because she was. She was flattered that the professor, who seemed to bestir himself for nothing and no one, was moved into some gallant action on her behalf when faced with the most noted harridan of the era. Of course, he hadn’t met Arsenic’s own mother, and he didn’t know what kind of resources Arsenic had as a result. But it was terribly sweet of him.

Since she’d as lief have his company either way, Arsenic allowed Percy to be gallant and didn’t tease him for it. She wished Rue wouldn’t. Percy seemed interested in her as more than a friend, and Arsenic rather liked the idea. She found his awkward mannerisms endearing, his conversation stimulating, and his skeletal structure pleasing. She’d never thought to pair up with a man, but he was exactly what she’d pick, if she did think about it. Also, she liked his cat.

There came a funny squawk at that juncture. (Not from Percy, as it turned out.)

What appeared to be some form of mechanized parrot fluttered down to land on the railing nearby. Arsenic thought mechanicals were illegal, but perhaps not in Egypt.

“Stay back!” yelled Tasherit, dashing forward with supernatural speed.

She caught it up with alacrity, and unceremoniously ripped its head off. Well, it was a bird and she was a cat.

“Was that strictly necessary?” asked Rue.

Tasherit handed her the broken pieces.

Rue poked about for a moment, finally extracting a note. “It’s from Mother. It’s their current address.”

Tasherit remained unrepentant.

“Give it here, chérie. I’ll see if I can repair it.” Quesnel held out his hand.

Rue passed the decapitated bird parts over. “No time, darling. They want us now, tonight. In fact, we’re already late.”

“How can we be late when we just got the message?” wondered Percy.

“You know Mother.”

Percy sighed.

Primrose appeared abovedecks perfectly turned out in a visiting dress of soft pink muslin, a matched beaded reticule, and an ill-matched but serviceable-looking parasol. She made a grabbing gesture with her pink-

gloved hand at Quesnel. “Give it here? I’ll put the parts in my bag. You are a vicious thing, aren’t you, Tash my darling?” There was approval in her tone.

Tasherit grinned at her.

“Poor petit oiseau. He was only doing his job.” Quesnel passed the parts over.

“Well, Aunt Alexia should know not to send birds to this ship. It’s lousy with cats.” Primrose was staunch in her defence of her lover.

Arsenic tilted her head, hearing a funny ticking sound. “Um, does anyone…?”

Tash apparently did, because she grabbed Prim’s reticule and hurled it full force up into the air.

The reticule exploded, showering them with pink beads.

Arsenic was amused to see that no one had flinched.

“For goodness’ sake,” said Rue.

“Self-destruct mechanism,” explained Quesnel.

“Yes,” snapped Percy, “we did deduce such.”

“Should have known, with my parents.” Rue was philosophical.

Primrose sighed. “I’ll never be able to find one better matched to this dress. Do I have time to change?”

“Don’t know why you were bringing a bag, anyway, Prim. Your parasol has more than enough pockets.” Rue didn’t sympathize with her friend’s accessory murder.

“There was an offering in my bag from my mother. I was to convey her warmest regards to Aunt Alexia… with fruitcake.”

“Your mother, the vampire queen, made fruitcake?” Arsenic wondered.

While Rue said, “Aunt Ivy baked? Well then, that might have been what exploded.”

Percy let out an exasperated breath. “Meanwhile, could we get on? Aren’t we already late?”

Tasherit was looking guilty. “I didn’t know it would explode.”

“Of course you didn’t, darling,” replied Prim.

“I’ll buy you another baggie thing, little one.”

“Pray don’t trouble yourself,” consoled the captain. “I’m sure Prim will find another reticule even better than this one, next time we are in Paris.”

“With tassels,” added Percy, in a certain flat tone Arsenic was beginning to realize passed for his version of humour

“Baggies come with tassels? Why did no one say?” Tasherit brightened.

“All reticules possess the possibility of tassel-dom,” added Percy, as if waxing thoughtful on some serious philosophical point.

Arsenic tilted her head at him. What was he about? “Are you claiming, Professor, that the tassel possesses, intrinsic to its nature, the ability to both exist and na exist, at the same time?”

“Where handbags are concerned, yes.”

“The professor reads Plato, I see.”

Percy’s lips twitched. “So does the doctor.”

Rue was glaring at them. “You two have to stop this kind of thing, at once. It’s most unnerving.”

Tasherit had big brown eyes fixed on her lover. “More tassels?”

“Percy! What have you done?” Primrose glared at her brother.

Arsenic tried unsuccessfully to hide a smile.

SEVEN

Bobbing for Parents

It was an exercise in drama and balance and, in the case of Quesnel, tolerance, getting Rue down the rope ladder (as opposed to the more civilized gangplank). She categorically refused to be lowered as if she were chattel. She would not use something called The Porcini, either, because it would take too long to inflate.

Arsenic insisted on going first, so that if Rue did fall, a professional would be there to pick up the pieces. Not that she thought it likely. In her opinion, pregnant women were more capable than most believed. It was only that this was a first for everyone, so all of Rue’s friends were overly concerned.

Nevertheless, the captain climbed down in one piece. Quesnel was next and the twins after, making that the sum total of their expedition party.

Arsenic wasn’t entirely sure why she’d been pressed into accompanying them, but she did admit to a certain curiosity over Rue’s parents. How does someone like Rue happen?

“How did your mother know we’d arrived?” it occurred to her to ask, as they walked through the city.

“I sent an aetherogram before we left London. She likely had the obelisks under observation too. But honestly, how does my mother know anything?”

Primrose nodded. “These days she’s almost as bad as Lord Akeldama.”

“What does she do, exactly, your mother?” Arsenic asked Rue.

“She and Paw run a tea business.”

“Oh aye, I remember someone said something about that. ’Tis na, uh, odd for an aristocrat?”

“To be fair, Mother’s only gentry, Paw holds the title. And in the end, tea gets shipped practically everywhere, and so goes Mother’s network. It’s called Tarabotti’s Tea.”

“Oh! I’ve heard of it. Excellent Assam.”

“See? Everywhere. Even Scotland.”

“And you want me along to meet her. Why exactly?”

“Arsenic, you’re part of the family now. You should meet our impossible matriarch. Everyone must.”

Percy looked like he was trying not to grin – an odd expression on his normally sombre face, as if he were attempting to swallow a live mouse. “Aunt Alexia is like an inoculation against smallpox, best to meet her at least once.”

Arsenic nodded. “Very well then.”

They hailed a steam-assisted camel cart of some mildly confusing arrangement, half modern technology, half old-fashioned pack animal. The camel and a steam engine existed in strange equilibrium. Arsenic was disposed to be pleased she wasn’t spat at, and happy to see Rue comfortably ensconced and not slogging along in heat and defiance.

Eventually they arrived at their destination.

“Well, that’s one solution, I suppose.” Rue regarded her parents’ new residence suspiciously.

It was not what Arsenic had expected. It was not what anyone ought to expect. She’d thought perhaps a palatial house, or a suite of rooms in a fancy hotel.

Lord and Lady Maccon appeared to have taken up residence in a house that was also a boat. Or a boat that was also a house. Like the narrow boats of the Thames dockworkers – only bigger.

It was, without a doubt, the oddest residence Arsenic had ever clapped eyes on. She supposed that if one had to move one’s house regularly up the Nile, as the plague zone shrank, and if proximity to water would make it easier on a preternatural to tolerate proximity to said zone, a boat did rather make perfect sense.

Rue rolled her eyes. “Of course, a boat, what else would they live in?”

Primrose was shocked. “My word, Rue! Your parents are itinerant vagrant river rats!”

“Prim darling, we live in a dirigible, what does that make us?”

Prim looked struck. “Good gracious me. We’re vagabonds! We’re essentially vagabond pigeons.”

Rue winced. “Can’t we at least be robins or something cute like that?”

Percy said, with a grin, “Anitra would call us Drifters.”

“It’s a loveliness of ladybugs. So can we be ladybugs?” offered Arsenic.

Quesnel cocked his head to one side. “It looks like a well-designed kind of boat.”

The Maccons’ boat-house-floating-thingy was about a third the size of the gondola section of the Custard, which made it respectably big, since presumably it didn’t have to house a massive engine room and boiler and storage and crew and so on.

There was no way to get onto it, however. The residence bobbed a ways away from the embankment.

“Tally-ho,” yelled Rue.

“Tally-ho yourself, Infant!” came an autocratic female voice back. Her tones were melodious and her intonations similar to those of Rue. Arsenic assumed that must be Lady Maccon.

“Rue, that you?” This time a loud male voice reverberated across the water. It was brash, deep, and raspy – very much as one imagined a werewolf voice ought to sound. Except this one was also distinctly Scottish.

“Paw, Mother, could we m

aybe come, uh, aboard? It seems silly to carry on yelling at each other over the Nile.”

“Oh yes, of course. Conall, would you be a love?”

There was a heaving sort of creaking noise, and a massive plank came whizzing down and hit the embankment with a crash, stretching over to the boat.

It didn’t look entirely stable but Arsenic supposed the worst that could happen was that one of them might fall into the river. She wasn’t the best swimmer herself, but she could mostly float. It was also hot enough that she wouldn’t mind cooling off. Why was sportswear always tweedy? She should have some bicycling outfits made up in muslin – in defiance of fashion.

Quesnel went first, although he ought not to, as he kept twisting about and nearly falling in an effort to keep an eye on his wife.

Said wife got mildly exasperated. “I’m fine, dear. I’m going slowly and I’m accustomed to being a bit off-balance. The plank makes no difference.”

Quesnel looked panicked by that.

“She’s not helping at all, is she?” said Primrose to Arsenic.

Arsenic shook her head.

After Rue went Prim.

Arsenic exchanged glances with Percy.

“I wish I’d asked you what I was in for.”

Percy grinned at her. “Lady Maccon? She’s a lot like Rue, only bigger and bolder and more practical. She’s all right so long as you don’t take offence easily.”

“Very astute summation of character, Professor.”

The man shrugged. “I don’t like people and I prefer not to interact with them if I can help it. Doesn’t mean I don’t understand the ones I grew up with.”

“Why did you really come along, Percy?”

“Honestly, for moral support.”

“Figuratively?”

“Literally. Lady Maccon has no soul, remember?”

“I wonder what you’d say about me, Percy, if someone asked.”

“So do I.” Percy’s voice had a funny note to it.

“And Lord Maccon?”

“He’s a big old softy, really. Adores his wife and daughter. Large. Scottish. Werewolf.” This observation was decidedly less astute.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

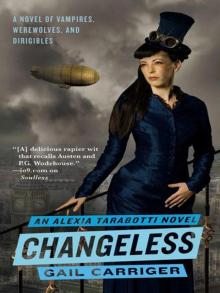

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

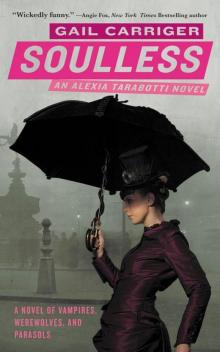

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

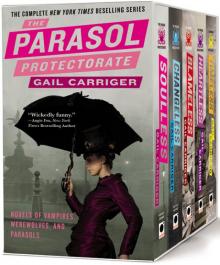

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

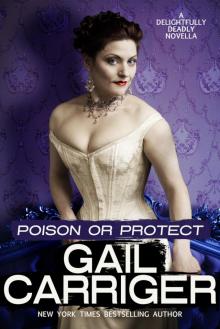

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

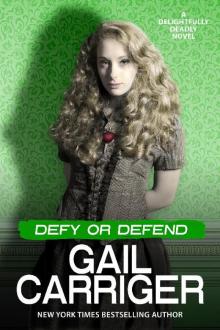

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3