- Home

- Gail Carriger

Ambush or Adore: A Delightfully Deadly Novel Page 2

Ambush or Adore: A Delightfully Deadly Novel Read online

Page 2

But in that moment, talking to a vampire behind the heavy velvet curtains of a too-expensive house at a too-indulgent party, she made the choice anyway.

“To be truly lazy, one chooses eternal life, no?”

The vampire laughed. “Touché, my little wallflower. Touché. I don’t normally recruit females. How very strange a creature you are.”

“I do not want to be your drone.”

“You don’t? Give yourself time. Youth always thinks itself eternal. In forty years, perhaps you will change your mind.”

Agatha considered the possibility of wanting to be a vampire. “I don’t believe so, but ask me again then. We shall see how much my character has altered by the time I’m fifty.” It turned out that this was a sentiment she would never regret and never change. One of the few.

“Do you believe you have excess soul, little button?” The vampire gave her an up-and-down assessment.

Agatha knew exactly what he saw. A plain girl, dowdy, regretfully redheaded and freckled, with a demeanor that was quiet, mild mannered, and invisible. There was nothing special or creative or excess about Agatha. She had nothing to carry her over into immortality and she knew it.

“Probably not, but that doesn’t make me worthless.”

“It does to most vampires.”

“And yet here you stand, my lord, talking secretly to a ten-year-old girl at a party. Are you rescinding your offer already?”

He chuckled. “I’m not most vampires and you’re funny. I didn’t think a child could be so diverting. It’s refreshing. Very well, I will see this done – as your patron, but not your master. Have you ever wanted to attend finishing school?”

“No.”

“Change your mind.”

“If you insist, my lord.” Suddenly, she liked him. He was full of plots.

“I will have one of my drones mention the name of one particularly interesting educational institution to your father. I will arrange to pay the fees and keep you in funds and attire. You will report to me what you learn there. And I do not mean the lessons. I mean the information that flows through the teachers and students. It is a very well connected school and you will emerge well connected and well educated because of it.”

“Finishing school, my lord?”

“The kind that teaches you how to finish everything, and not just your supper.”

“Even vampires?”

“Especially vampires. However, you are to avoid attracting any kind of attention whilst you are there, even from vampires. Especially from us.”

“I will endeavor to be the best while pretending to be the worst.”

“I have no doubt.”

Without sparing her another glance, Lord Akeldama slid out from behind the curtains. He became once more the darling of the assembled, the prince of witty repartee, and the object of many adoring eyes.

Agatha had bargained with a monster at age ten. He wore sunset purple satin and gold lace, and he would be her closest ally for the rest of her life. Perhaps it was a devil’s pact or perhaps it was a gentleman’s agreement. Since Agatha was neither gentleman nor devil, she would only learn the price much, much later.

Decades later, she would calculate the cost on the deck of a fancy dirigible shaped like a ladybug and crewed by eccentrics. She would think of that payment not in terms of the scars she bore and the blood she’d risked and lost, as a vampire might, but in terms of her disaffected heart. That one thing she’d held too hard in reserve and never risked at all.

But still, she would never regret the bargain she’d struck.

She began attending finishing school three years later.

Pillover Plumleigh-Teignmott, on the other hand, did not remember his first vampire at all. Unlike Agatha, he’d never had a defining moment of clarity connected to the supernatural set. He had been mildly annoyed when a vampire queen kidnapped him. But even that hadn’t had a profound impact on his life in the long run. He’d grown up around vampires, werewolves, and their sycophants. His parents, being evil geniuses, dealt with the supernatural set on the regular. There were always drones and clavigers coming and going from their country house. At various times the family would take residence in one of the lesser known but more refined neighborhoods. Then, there had been vampires. Pillover had confessed to Agatha once that he felt that he ought to have remembered his first. But he’d been too young.

His parents had dealt with the inconvenience of children by carting them everywhere and mostly ignoring them. This left Pillover and his sister to entertain each other. Which, as he was the younger, mostly meant his sister dressing him up and treating him like a living doll. This might have turned an ordinary schoolboy evil, but Pillover hadn’t really minded, and perhaps this made him more sympathetic to vampire drones than most. It did, however, give him a near virulent disregard for fashion. As much as his sister loved fripperies and fobs, he was disposed to dislike them intensely.

When Pillover was shipped away to school at eleven years old, he was in his oversized bowler and oiled greatcoat stage. He had spectacles that were very thick, a brow that was very creased, and a large, dusty book normally occupying the entirety of his lap and attention. This persona had allowed him to resist his sister’s efforts of late and remain ignored by his parents. But it served him ill at Bunson and Lacroix’s Boys’ Polytechnique.

In short, he arrived at evil genius training academy already younger than most of the students, and instantly became the preferred whipping boy for anyone who thought they were better than he. Which, as it turned out, was most everyone else at Bunson and Lacroix’s Boys’ Polytechnique.

It was a cruel thing his parents had done, sending him to an evil genius school. But as they were both evil geniuses themselves, he ought to have been better prepared. Perhaps Pillover should have paid more attention to those vampires – they were supposed to be some of the best at being evil. His father was a founding member of the Death Weasel Confederacy, and his mother was a kitchen chemist of questionable intent, but Pillover was just bad at being bad. He had the genius bit in hand (well, he did if you asked him about it) but he was not and never would be at all good at being evil. Which meant, of course, that everyone else got to practice their evil on him.

The Pistons made his life at school particularly horrid. Strutting about in riding boots and black blouses, sewing cogs onto their outfits in a non-useful manner. (This last affectation was particularly egregious so far as Pill was concerned. Not that he was a mechanic or an engineer, but it was just so wasteful.) The Pistons used their aristocratic connections and their club rules as an excuse to push him around. Apparently only Pillover believed they attended school to learn things.

Fortunately, he only had to survive eight years of it.

Eight years.

And then they introduced girls into the mix.

It was absolutely awful. A tragedy.

Autumn 1851 ~ Mademoiselle Geraldine’s Finishing Academy for Young Ladies of Quality, somewhere over Devon

Agatha would have survived finishing school no matter what, but much to her surprise, she made friends. And friends, it turned out, made everything that much easier. The teachers were strict, the classes were hard, and most of the girls were both pretty and pretty darned mean. But, so far as Agatha was concerned, anything was better than her father’s household, and she would do whatever she could never to return.

The friends were unexpected. In many ways an added burden, as she had to lie to them, too, while sending her regular reports back to Lord Akeldama. She tried not to have to do it too much, and she tried to be as genuine and kind as possible. They were, after all, at a school for spies and assassins – intelligencers. She hoped that they would forgive her a minor, if extensive, double crossing.

She ended up liking her friends quite a bit. And, much to her shock and amazement, they seemed to like her back. Sidheag was the first to win her over. Agatha was grateful they’d been told to share a room, for it was the Lady of Kingair who introd

uced her to the others. Tall, grumpy, and Scottish, Sidheag Maccon came off as gruff, but turned out to be kindly underneath it all. Sidheag saw none of the usual flaws in Agatha’s timid manner, dumpy appearance, or awkward address, because Sidheag saw only actions, and Agatha was never cruel. In fact, Agatha never did anything to attract any kind of attention at all. She knew where her talents lay. And while Sidheag never noticed the intent, she actually really liked that Agatha was a wallflower.

After Sidheag came Sophronia – proud and cunning and a little bit scary. After Sophronia came Vieve – tiny, fierce, and irrepressibly mechanically minded. Trailing Sophronia, like a very sparkly puppy, was Dimity, the easiest to like of them all. Dimity was chattery and sweet. Agatha worried about her sometimes. Because her parents might be evil, but Dimity had inherited none of it.

Finally, after Dimity, came her younger brother, Pillover. He turned out to be even softer than his sister, so Agatha worried about him most of all. He was a brilliant, sullen boy, full of sarcasm and concern. Complaining even as he always helped, no matter the cost to his own life and personal preferences. He was a lumpy bundle of grumpy loyalty that Agatha felt none of them really deserved, least of all herself. Yet he gave them all equal parts annoyance and affection, unreservedly, as if he had no choice. As if he felt they were worthy merely by virtue of being his sister’s companions.

Sophronia basically conscripted Pillover into her – and consequently their – shenanigans by default, and then kept him around because she found him useful. Sophronia found odd people useful. Agatha didn’t meet Pillover right away. After all, they were in a girls’ school floating about the clouds, and he was at a boys’ school in a secret location far below. But Agatha did hear about him on those rare occasions when Dimity was moved to talk about family. Which wasn’t often. Having no siblings of her own, Agatha couldn’t sympathize with Dimity’s complaints about her “pustule of a brother,” but she could imagine the frustration.

When Agatha did meet Pillover, she very much liked him from the start – glum but restful, and quietly smart about Latin, if not people. Agatha didn’t learn Latin, but she appreciated a boy who obsessed over something so obscure. She thought it showed strength of character not to be taken in, like the Pistons, by rank and appearances, but instead to be taken in by the secret knowledge of an ancient world. After all, she had been taken in by the secret knowledge of this one.

Not that her liking him mattered all that much.

Not at first, anyway.

Pillover got occasional notes from his appalling sister for the first six months of school. They came sporadically because mail had to wait until her school floated close to some acceptably rural village or other. He did not hear from his parents. They weren’t the floating types and had nowhere near his sister’s excuse, but they were probably distracted by corrosive capybara carcasses or something equally vile.

Pillover would never admit that he looked forward to Dimity’s funny sideways rambling, but he did. He read about her new friends. She was the type to make friends easily. He wasn’t convinced that he envied her that. Apparently her friends numbered only three, so she wasn’t that good. He’d met Sophronia, who was very smart and good fun (according to Dimity) but whom Pillover had found rather brash and excitable. Sophronia was the type of forward female who enjoyed adventure and physical action, both of which Pillover deeply mistrusted and somewhat feared. Still, he didn’t have to put up with her, Dimity did.

Dimity wrote of others – someone named Sidheag who was Scottish and had been raised by wolves (which Dimity found exciting but also rather scandalous), and another one named Agatha. What Dimity had to say about Agatha could be summed up in four lines of text.

My new friend Agatha is sweet and gentle, but I worry about her because she lacks sparkle. Our school is not a good place for such a person. She is also somewhat shy. If she is to last, we must look after her.

Pillover therefore liked Agatha best of Dimity’s friends well before he actually met her (purely on the grounds of four lines in his sister’s rather flowery prose). But that was all he knew of her until the following term.

Pillover never dreamed he’d get to see the inside of his sister’s school. It was, after all, a massive floating dirigible for girls alone. Yet, eventually he found himself wandering the halls of Mademoiselle Geraldine’s Finishing Academy for Young Ladies of Quality, confused about life. Of course, he was newly thirteen years of age, so he was always confused about life. But this made things worse, to be one of only ten boys surrounded by girls. Surrounded by the enemy. They were there for a trip, a special treat. And he’d been included only because he had a sister on board. (Or so he’d thought.) It was supposed to be a good thing. A reward. Floating along with all those girls on a special jaunt into London on a massive dirigible.

Pillover hated London.

Pillover did not like girls.

And frankly, he wasn’t sold on dirigibles, either.

He remembered only snippets of that first visit. The way the lighting overhead looked like parasols. How still the school was – it didn’t feel like it was floating at all, but it also didn’t feel like it was grounded.

Pillover thought that memories were like dust motes of time. They inhabited the air around him but he never noticed them unless the sunlight struck just right, or they made him sneeze. Most of his years at school were long since dissipated into the aether, moted and hazy. But sometimes, some bit would sparkle just so and he would find himself sneezing with memory.

He recalled perfectly what it felt like to walk into the dining hall and see the faces of so many girls staring at him. Pretty, eager, chatty females craning their necks and staring at him, like a massive flock of multicolored flamingos at tea. Deadly flamingos. Pillover found every part of the situation terrifying, even the tea.

Except that he, and he alone, had familiar faces to search for. There was his sister. And there was Sophronia. And there next to Dimity sat a slumped, frightened-looking girl with red hair whom Pillover guessed was Agatha. She looked even more frightened than he felt, which was oddly comforting.

Not everyone is lucky enough to remember their first impressions. But Pillover never forgot Agatha’s frightened face. Possibly because years later he would realize how false a face it had been. Would become afraid that his first impression of the love of his life had been entirely fake. Or had it? That was the game his brain played on him where Agatha was concerned. Questionable memories were parceled up with her questionable identity.

They were all undertaking a trip to London. Pillover was assigned to the dining table with Sophronia for the duration. She was a good egg whom he liked, insofar as one could like a girl and think of her as in any way eggish. In her usual fashion, Sophronia had him under her wing and doing several odd things after only a few days aboard (including writing to his parents because she thought someone was threatening his sister). Ordinarily Pillover would have been disposed to think of this as feminine hysteria, but not with Sophronia. Not that he was inclined to argue or disobey her instructions – no point, Sophronia would win regardless. She was like that. Girls were, frankly, in general like that. Pillover supposed he was destined to be one of those gentlemen entirely ruled by his wife. He considered this, and then resigned himself to his fate and stuffed his face with better food while he could.

They did have superior comestibles aboard the dirigible. Bunson’s meals were notoriously bad, as though the food were also trying to be evil, but Geraldine’s girls enjoyed a varied and respectable diet. Partly because they were supposed to learn all the appropriate cutlery and etiquette for every possible cuisine, and partly so they could taste the various flavors and work to understand which poisons were best hidden in what dishes.

His sister was in some kind of mood through most of the trip, ignoring both him and Sophronia, which Pillover took as a godsend. He left it up to Sophronia to figure out what was going on and simply tried to survive the sea of indistinguishable, terrifyi

ng femininity. There was a kind of evil to girls that even he, at a school for the stuff, couldn’t fully comprehend. A circulation of carefully calculated compliments that weren’t and small, petty digs with huge significance. He found everything about it exhausting.

Eventually, Dimity and Sophronia made up their differences and Pillover found himself spending the remainder of the trip in the bosom of his sister’s friendships. He got to meet Sidheag, who was pleasingly brash and unrefined, but regrettably Scottish. He rather preferred his languages dead and not complicating current-day vocabulary. He wasn’t even confident in English, which seemed a messy sort of barbarian language, always stealing from others. And then, of course, Agatha.

Agatha never chattered. Pillover considered chattiness the worst flaw in a girl, so her quietness was beautiful. Agatha seemed to enjoy fading into the background, an instinct Pillover understood all too well. But it made him want to watch her more than the others.

A lot happened on that trip. He even got kidnapped by vampires – messy business. A lot that he forgot and only bits of which he could recall given the right incentives. Memory was a funny old thing. But what he recalled most clearly was dancing with Agatha for the first time.

He remembered how restful she was compared to his other partners. She didn’t try to talk. If he mentioned something Latin, she never acted confused or overly interested – just nodded. She was taller than he back then, a worldly fifteen to his thirteen. He remembered that she felt graceful in his arms, as if she were going easy on him. He thought that maybe her clumsy gawkiness with other partners was a sham and he wondered why. He considered asking her, but felt that would be intrusive. So instead he just enjoyed that she was round and soft and that she didn’t say anything except with her eyes. They were big and a kind of watery greenish color, like a pot he’d seen once in a museum. Celadon, it was called. He thought they were also sad. Pillover, who spent most of his time being intentionally morose, rather admired a winsome misery in others. He wanted to ask her what was wrong. But he never did.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

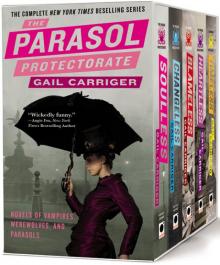

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

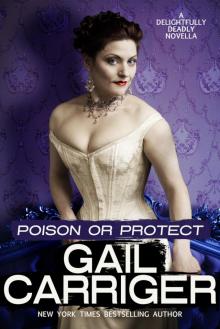

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

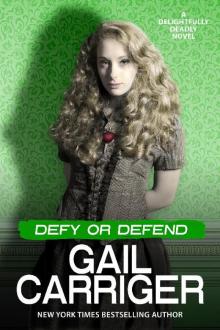

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3