- Home

- Gail Carriger

Imprudence Page 27

Imprudence Read online

Page 27

“Interesting,” said Floote. As if Tasherit’s one statement had changed his whole perspective on the situation.

The werecat flashed them both a wide smile. “Drifters like cats.”

Then suddenly, just like that, she shifted form. A large lioness stood on hind legs next to them, with paws against the railing and tail swishing behind her.

Instinctively, Rue raised her hand to provide the necessary control with touch. She looked to the moon. It was not full.

Miss Sekhmet shook herself, like a dog after a swim, her thick golden fur silvered in the moonlight.

With instinct dampened and safety assured, Rue realised that she, too, had felt it lift. The numbing oppression that surrounded her since they entered Egypt was gone.

They were outside of the God-Breaker Plague.

FIFTEEN

Coal and Consequences

It took them another full day of floating to meet the Nile again where she bent, eastwards this time, below the tiny Nubian village of Abu Hammad. There the dervish met them with a porcupine of bristling guns. Rue had no interest in encountering those whirling automated cannons. They gave the town a respectably high float-over.

Several miles upstream, the Nile narrowed, digging out a deep undulating blackness with sheer cliffs to either side. Miss Sekhmet scented the air, pronounced it safe, and they dipped down to the river to take on boiler water.

At Quesnel’s request and Spoo’s big eyes, Rue allowed the crew a short swim. They deserved some little luxury. Rue envied them their delighted splashing, but it was beneath the dignity of a captain, let alone a lady, to submerge herself in water. That was assuming Rue could swim, which she could not. In fact, Rue had never been a great bather of any kind. There was something about being surrounded by water that made her feel dulled, half her senses cut off from the world, rather like the God-Breaker Plague. She preferred a shower, although rarely available, or a sponge bath.

Quesnel, who had no dignity, joined the crew. He kept his smalls on, although the way the cloth fairly stuck to everything, he might as well not have. It seemed more scandalous than nudity. You’d think, since she’d seen it all already, Rue could pull her eyes away. But she was hypnotised watching him cavort about, tossing Spoo and Virgil up into the air. The youngsters shrieked in delight.

“Lovely.” Tasherit came to watch. She shared Rue’s abhorrence of bathing.

She was shrouded in robes to protect her from sunlight, wearing a hat and carrying one of Prim’s surviving parasols. She looked tired. Were she the type to obey, Rue would have ordered her back to her quarters to sleep the day away like a respectable immortal.

Orders being wasted on cats, Rue said instead, “I didn’t think you favoured men.”

“I make exceptions. However, in this instance, I wasn’t looking at your pet. See, there?” The werecat pointed to where Primrose joined the bathers.

Prim was in a full swimming costume, navy blue with white piping. She was a darn good swimmer for an aristocrat, as was Percy, who paddled next to his sister in a striped costume of white and red contrasting with his hair. Incongruously, he wore a top hat as he bobbed about.

“Oh, sir.” Virgil was distracted from his play into noticing his master. “This is the one time you are supposed to leave off your hat!”

Percy only floated by, looking dignified and pleased with life. Rue would never have thought Percival Tunstell fond of a nice swim. Funny, she had known the twins her whole life. When had they become sporty?

Primrose completed her exercise and went to paddle in the shallows, retrieving a wide-brimmed straw hat. Even damp she was pretty as a picture, her waist enviably small without a corset. Rue sighed. She’d never have Prim’s figure, not without giving up her beloved puff pastry for ever.

Tasherit couldn’t take her eyes off the girl.

“She’s not ready for you.” Rue wanted to urge caution without discouraging too much.

“Can’t help chasing. It’s my nature.”

Rue grinned. “I think perhaps you are old enough to control your nature, should you really wish it. Admit it, you like chasing.”

“It’s been decades since I’ve been this intrigued.”

“Well, tread lightly.” Rue wondered if she ought to stop this conversation. Primrose was her dearest friend; she didn’t want to say anything that would betray that friendship.

“That, too, is in my nature.” The werelioness smiled. Her liquid brown eyes gleamed when Prim laughed at Quesnel and Spoo’s antics. “I’m patient.”

“You’ll have to be.”

“She’s special.”

“I know.”

“He’s special, too.” They both knew the werecat was talking about Quesnel.

“Don’t matchmake me, old godling.”

The werelioness wheezed out a laugh. “Mortals! Everything is fuss and bother with you.”

At that, Rue decided it was time to hurry everyone back aboard.

Rue watched Quesnel that evening at dinner, more than usual. He was solicitous of Anitra, even attentive. He also took great care of Floote. Really, Quesnel flirted with everyone, except maybe Percy. He’d probably flirt with Percy if they hadn’t been perennially at odds over the finer points of academic publication theory.

After dinner, when the gentlemen would have gone to partake of brandy on one side of the deck while the ladies drank sherry on the other, Rue put a hand on Quesnel’s arm.

“A private word, Mr Lefoux, if you would be so kind?”

The others looked curious but no one was brave enough to insist on a chaperone.

Quesnel followed Rue belowdecks to the stateroom.

Rue didn’t know what he was expecting, but from his expression it wasn’t what she asked. “Quesnel, have you figured out a way to determine excess soul?”

His answer was flat, with no artifice to it, almost shocked. “No. Of course not.”

Rue let out a breath of profound relief. “Oh good. Because a whole lot of people would want to kill us if we had that technology on board.”

Quesnel frowned. “It would save lives. To know beforehand if someone could survive the bite. It would be a miracle.”

“It would also limit the number of people who would petition to be drone or claviger. Society as we know it would collapse. Vampires would have much less blood to draw on and werewolves fewer guards at full moon. Both would have to hire out. The balance of power would shift.”

Quesnel nodded. “It’s not possible to measure the soul, last I heard. Although there is always someone researching it. It’s only a matter of time.”

“Well, I hope I’m not in London when it happens.”

“Why did you think I might, chérie?”

“That preservation tank of yours. You brought it with us on purpose. You brought it because Mr Floote is dying.”

Quesnel didn’t try to deny it. His face shuttered.

“Is he particularly creative? Do you think he has excess soul?”

“Mother says the man always did come up with the most original cravat knots.”

“Is that enough?”

“He expressed a fondness for flower arranging.”

Rue quirked an eyebrow, hoping she looked sardonic.

“He fights as if he were dancing.”

“My grandfather’s valet, my mother’s butler, fights?”

“According to maman, quite beautifully.”

“So the preservation tank is for him. Why?”

“He knows too much.”

Rue narrowed her eyes. “According to whom? Your mother? The OBO? My mother? Someone else? Who are you really working for, Quesnel?”

“I’m working for you. For this ship.”

Rue snorted.

“You don’t trust me at all, do you?”

“Give me one good reason why I should?”

“I can give you ten; my chamber is right down the hall.” He moved towards her.

Rue wanted, very badly, to lean in to those clev

er hands and that sweet mouth. But he was using both to avoid conversation and she knew it. “Quesnel, I trust you to be very good at what you do, under an engine or a coverlet. And I trust you to take that expertise to the highest bidder, in money or beauty.”

Quesnel put a hand to his chest as though mortally wounded.

Rue gritted her teeth at his flippancy. “Oh for goodness’ sake.”

“You already have your answer, chérie. I’ve given it to you. Think. Who would want a man preserved because he knows too much?”

Rue’s mind clicked over, like a slow but inexorable cog. Who had insisted that Rue put Quesnel to work in engineering? Who knew Quesnel’s patroness of old, when Countess Nadasdy and not Baroness Tunstell had ruled the London hive? Who could afford to invest in a preservation tank – new technology at great expense – on the mere whiff of an old man’s memory?

“Dama,” said Rue. “Blast him. Why didn’t he tell me? Why didn’t you?” He’s trying to meddle from afar!

Quesnel gave one of his French shrugs. “It’s morbid, non? Perhaps he was trying to protect your finer sensibilities.”

Rue narrowed her eyes. “Or perhaps Floote knows something Dama wishes me to know. Perhaps this is Dama’s roundabout way of helping, of trying to keep me safe.” She was thinking about her conversations with Floote concerning her mother’s past and all the things he hadn’t told Rue about her grandfather.

Quesnel shrugged again. “Information is vampire currency. I shouldn’t take it as an intentional slight.”

“No, you wouldn’t.”

“What’s that supposed to imply?”

Rue examined the world through her eyelids for a moment. Her nerves hummed, from anger, or discovery, or Quesnel’s proximity it was hard to determine which. Unable to cope with any of it, she left the room.

They abandoned the Nile for the desert once more. At one point they saw, far away in the rocky sands to the west, the black smoke of a nomadic centacopper. Powerful, town-carrying, mechanical turtles of the great empty, those major feats of engineering could crawl over the desert for weeks on little fuel and less water. Quesnel came up from engineering at the first word of a sighting and kept his amplified glassicals trained for as long as he could.

“I’ve always wanted to see one up close.” He seemed wistful. Almost subdued.

Rue was briefly tempted to hare off in pursuit of the centacopper; perhaps then Quesnel would smile again. But she was not so foolish. If only, she thought, we really were a ship of exploration and not a ship near constantly under siege.

“See?” Primrose also noticed Quesnel’s odd behaviour, later at supper. He had said only the nicest and most politic things and then left early. “Happy now?”

Rue narrowed yellow eyes at her friend and mouthed, “Not now.” Anything Prim had to say to her in that particular tone of voice was best kept for private chambers.

They retreated there as soon as politeness allowed.

“Out with it.” Rue faced her demons as soon as they were alone in Prim’s room.

“You’ve broken that boy’s heart.” Primrose was getting rather dramatic, even for Aunt Ivy’s daughter.

Rue let out a burst of surprised laughter.

Primrose was not amused. “Oh, stop it. What is really going on?”

Rue paused to examine her feelings. What was really going on? Finally she said, before she could stop herself, “I don’t trust him not to break my heart.”

Primrose sat back with a whoosh noise, pensive and startled at the same time. She took a small breath and spoke slowly, choosing her words with care. “So you break his first? That’s hardly sporting.”

“I didn’t think his heart was something I had power over.”

“So are you doing this simply to prove that you can? I did think, from an outsider’s perspective” – she blushed – “that you were good together. Was I wrong? Did something not work in, you know, that way?”

Rue considered Quesnel’s mouth and hands, the smooth feel of one and the rough feel of the other. She considered his eyes, up close, violet twinkling. It had been a great deal of fun, his lessons. Was there something wrong with fun? She was usually in hot pursuit of adventurous pleasure in all other parts of her life.

“Quite the opposite.”

Primrose pressed.

“So you are in love with him?”

Rue shied away from that idea. It was utterly terrifying.

Later that evening, Rue unexpectedly encountered Anitra alone on the poop deck. She would have turned to leave the girl in peace but, at a welcoming gesture, joined her. They stood companionably chatting, looking out over the dark desert.

Pleasantries exchanged, Anitra said, quickly, as though getting something pent up out, “Captain, I wish to say something. I do hope you will not take it amiss.”

“Yes?”

“I wear no dowry coins.” She gestured across her forehead where the edge of her veil rested. “Nor do I wear anklets or bracelets.”

“I had not known to remark upon this absence but I do now.” Rue was a little confused but it was her business to be polite to a guest.

Anitra bit her lip. “Very well, then, I should… um… good evening.” With which she left.

“Well, that was odd,” said Rue to the night silence.

“What was?” Miss Sekhmet emerged abovedecks, looking fresh and chipper. They’d settled happily into their old immortal cycle where she joined them for supper after sunset and then took the night shift. They missed her company during the day, but it was healthier for her not to fight the nocturnal habits of several lifetimes.

“Miss Anitra just insisted on telling me that she wore no jewellery.”

Tasherit grinned. “She was informing you that she is not available for courting. Did you make a move in that direction?”

“Certainly not.” Rue thought of Ay and that fact that Anitra might perceive her as masculine. “At least, I don’t think I did.”

The immoral nodded. “Ah, so. Then it is your jealousy when Quesnel pays her too close attention. She is trying to make clear her lack of intent.”

Rue drew herself up. “Pardon me!”

“No need to fluff up, child. If you do not wish your feelings known, hide them better. On this ship, the only one unaware of your interest in that mechanic is that mechanic. And possibly Mr Tunstell. But Mr Tunstell would remain unaware of a sand tick up his nose.” The werecat grinned at her own wit and returned to the point. “Anitra is merely informing you that she is not after your man. A female Drifter without dowry on display is not available.”

Rue was forced to accept that she had not been subtle. She would have to sort this mess out before others were drawn into it as well. It was most complicated, being the captain of a ship.

Of course Rue avoided both Quesnel and the mess for the next two days. Instead she dogged Floote, asking him about the past, when he let her. She soon realised that she was telling him more than he was telling her. She found herself reliving her peculiar upbringing with three parents and two households. She reminisced about the things those parents had taught her, which until he asked she’d forgotten. She told the more recent stories of the pack’s rejection and about Queen Victoria’s anger and Dama’s concern over her majority. Rue began to suspect that Floote said so little because others found him easy to talk to.

At which point, they reached Khartoom. The city sat at the junction of the White Nile and the Blue Nile. This was rummy-looking from above; for leagues they could see the two rivers meet but stay parallel, not intermingling, the brown of the Blue Nile alongside the green of the White Nile. The city took her mechanical power from these waters. All along the banks, dozens of great watermills, or what looked like watermills, spun and whirled, casting droplets to the sky. Khartoom was a beautiful city, all lush green with spires of white. It was also decidedly unfriendly to both Drifter balloons and ladybug airships.

“Odd names for rivers neither white nor blue.” Rue chewed a bit

of candied orange peel and stared down at the water.

Anitra smiled. “We don’t question the ancients.”

“No? Why not?”

Several red handkerchiefs were waved at them from Ay’s balloon. Anitra waved back, and as a group, the Drifters caught a breeze eastwards away from the city.

“They’re abandoning us?” Rue tried not to sound forlorn.

“They’ll meet us on the other side. We’re less of a threat without their shadow. They’ll keep a long-distance eye on us.”

“Khartoom looks calm enough.” Rue watched their escort drift away.

“It’s been under siege at one time or another for as long as I can remember.” Anitra seemed to think that was explanation enough.

Rue swallowed her last bit of peel, looking with sudden suspicion at all the lush graceful peacefulness. “Who holds it now?”

“You didn’t check with the council in Cairo before you set course?”

“Didn’t know we were coming here, exactly.” Rue was put off by the accusation in her tone. And her own guilt. She should have thought to make enquiries. Then again, enquiries would have left a record.

“The Mahdists hold it, but they’re stretched with forces out at Adwa. They took some of Khartoom’s major defences with them to roust the Italians. It leaves Khartoom vulnerable, and nervous about it. I wouldn’t go to ground if I were you.”

Rue slouched in dejection. “We may not have a choice.”

She put in a call to engineering, not sure if she was more reluctant to talk to Quesnel or Aggie. No choice—Aggie answered.

“Miss Phinkerlington, how are coal reserves?”

“Pants, Captain.”

“No need for vulgarity.”

A snort met that rebuke.

“How many days?”

“No days. Hours.”

Rue hung up the speaking tube, cursing herself for not putting a system in place that warned of low reserves. I suppose if I were on speaking terms with my chief engineer and not bent on avoiding him for days at a time…

She returned to Anitra at the railing, glum. “No choice. We’re dry. Will they even sell coal to us?”

Romancing the Werewolf

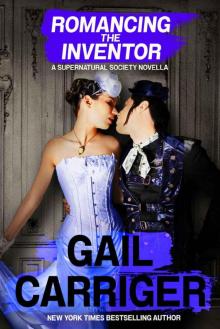

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

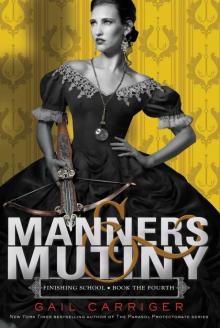

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

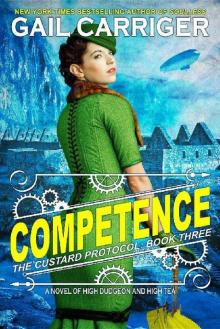

Manners & Mutiny Competence

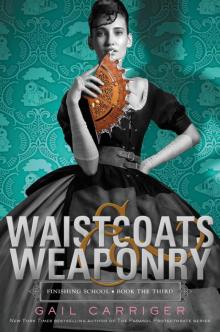

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

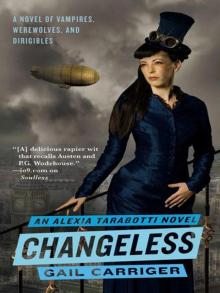

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

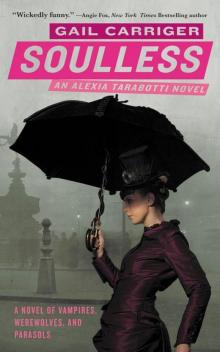

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3