- Home

- Gail Carriger

Funny Fantasy Page 6

Funny Fantasy Read online

Page 6

The greatest disappointment in Dagmar's life was that Henry did not appear to be likewise infatuated with her. She ascribed this, given her deceptively unremarkable appearance, to his simply not having noticed her. She set about to remedy this.

On the eve of the coldest night of the year, just after the last murmur of the fish jangles had died away, Dagmar stationed herself below the tower looking up at the fish chamber fifty feet above. In her hands, she held her uncle's bangy-wurdle, salvaged from the dowager Batterfly's lumber room. Bangy-wurdles were the instruments of the insane, the bizarrely eccentric and the lower classes of society. No one of good breeding would even admit to owning one. The instrument produced a music often described as "a din of iniquity."

Practicing in secret, Dagmar had spent the summer learning to master the instrument. She reasoned it thusly: a piano was too difficult to drag to the town square, and a clarinet didn't allow for singing. And sing she did. She sang a song she had composed for her love, amidst daydreams of his froggy hands, his simian limbs and his days at play among the shining fish. At the close of the second verse, as she launched into the chorus, she saw a white face thrust out from the tower window.

"What's that fuss?" said Henry. "Are you ill?"

She finished the chorus and shouted up to him, "A song professing my love for you, dear Henry. Sit back and enjoy while I serenade you." And she continued to play what was later described by the town wag as "the musical equivalent of a cat caught under a pram wheel."

Despite several pleas from around the square for Dagmar to hold her peace, she played on, singing of Henry's attributes.

"My what?" Henry shouted. "What are you saying?"

"Your glorious shining fingers," she shouted back.

There were some hoots of laughter from one of the nearby houses.

"Clear off," said Henry. "People will hear you."

"You are the most desirable man in the Vale of Brecon, and I am not going to stop until everyone knows it." Dagmar continued to play. She had not quite finished her fourth turn through the chorus when Henry, desperate to shut her up, emptied a water pail out of the tower window. The air was so cold that the cascade had nearly crystallized by the time it broke over Dagmar's head. Dagmar squeaked in shock and almost dropped the bangy-wurdle on the cobblestones.

"Now go home!" said Henry. And he banged the tower shutters closed.

Dagmar took a few moments to collect her wits, shaking the beads of ice from her coat and brushing them from the bangy-wurdle. Her hair was now frozen into points.

Lydia Batterfly's house abutted the square, and Dagmar retreated to it. There was no point in further stating her suit if Henry had closed the window. Unfortunately, as soon as she tried to open the front door, her wet hand froze fast to the metal knob. Try as she might, she could not get it free. Her shouts for assistance were met with answering shouts to shut up. Eventually, though, they drew her fondest friend Eora, the duchess' daughter, from the house next door. Eora was of that sensible type who are really quite wonderful in a pinch, though they tend to be dull and full of advice for living a good life at other times. On this occasion, Eora, who'd watched the entire spectacle from her bedroom window, came prepared carrying a bowl full of hot water from the kettle. The bowl had contained some exotic fruits which were now dumped over her mother's oak dining table. Eora proceeded to pour the steaming contents of the bowl over Dagmar's hand in an attempt to loosen it from the doorknob. The major difficulty being to stop herself laughing so hard that she dropped it.

"Yes, all right, all right," said Dagmar peeling her hand from the door handle. "It isn't funny. I mean, you have no idea what love does to a person. You'll see."

Though really, Dagmar thought, Eora was the sort of person who would fall in love—or something respectably close to it—with a suitable gentleman approved by her mother the duchess, and they would be wed in a ghastly ceremony in which Dagmar would be forced to attend in some abominable dress. Dagmar loathed dresses.

WORD GETS ABOUT in small places, and it wasn't long before Eora's mother, the Duchess, was informing Lydia Batterfly of what Dagmar had been up to while she had been out of town.

"She's sending me back to finishing school," said Dagmar to Eora that afternoon.

"Not again! That's what...The fourth time? What are you going to do?"

"Third, and I think she's going to find that Madame Loge will have nothing to do with me. She doesn't like to be reminded of her failings. They're so few and far between. As to what I'm going to do, I've thought of another plan."

"Plan?"

"To win Henry."

Eora stared at Dagmar and said nothing. Perhaps it was a tactful omission of words. When at last she spoke, she said, "What are you going to do?"

"Come with me and see," said Dagmar. She led the way down the center of the street, down the narrower alleyways of Brecon town, to Tyrone's Fishing Tackle Emporium.

"What on Earth?" Eora muttered.

Dagmar went inside and accosted the shop's proprietor. "I would like your best and strongest rod, please."

"Yes, madam," said the proprietor. "We have a variety of—"

"The longest one you've got."

"Oh," said the merchant, and he led her to the window of the shop from which he pulled a small brass cylinder.

"That doesn't look very large, man," said Dagmar.

"If you would come outside." The merchant stepped out into the street and proceeded to extend the rod. The mechanism was a telescopic one. The merchant pulled each joint out, lengthening it until it stretched the entire length of the alley and protruded out over the High Street sidewalk. Curious onlookers peered at it warily and walked around it.

"Well?" said the merchant.

"I suppose if that's the longest one you've got, it will have to do," said Dagmar. "How much is it?"

"Oh, madam, workmanship like this... This is a one-of-a-kind, made on the Gwyntog Coast and designed after the one used by Martidel Bayliss who once fished with it in the ocean. It is the most beautiful piece of wo—"

"I'm amazed you're willing to part with it."

"I could be coerced," said the merchant. "But it would take a king's ransom."

"Far be it from me to part a man from his beloved rod. We'll look elsewhere, thanks."

"You will not find a larger or better rod in the entire Vale of Brecon."

"That's as may be, but I haven't got a king to ransom."

"Perhaps we could negotiate."

A price was settled, though the merchant claimed he would go bankrupt, and Dagmar claimed she would have no dowry, "Though without this, there would be no need for a dowry."

"Why, Dagmar?" said Eora. "What are you going to do?"

"I," said Dagmar, "am going to catch the Barbary Fish, and then—"

"You're out of your mind!" said the merchant. "You?! The best fisherman in the history of Brecon spent his entire career trying, and even he couldn't catch the Barbary Fish."

"Please," said Dagmar. "You interrupted me. As I was saying. I am going to catch the Barbary Fish and present him to Henry the tower boy as a token of my love."

"Dagmar..." said Eora.

"I know," said Dagmar. "I'll need bait."

Dagmar strode off waving her rod, now telescoped down to a more manageable twelve inches. Eora was forced to run to keep up with her. Dagmar led her to the fishing grounds at Leechfield. The day was gloriously clear, and there were several fishermen sprawled amid the long grasses, eyes following the spiderfloss of their fishing lines which disappeared into the sky, ending at their lures glinting from colorful balloons. High above them, the braver fishermen rode in baskets beneath larger balloons, harpoons held at the ready, sighting along the Vale for the cloud-wisps of fish-spoor.

Dagmar made straight for the oldest and raggedest of the veteran fishermen at Leechfield and without preamble, said, "If you were to try for the Barbary Fish, where would you set your line and how would you bait your hook?"

The man

looked at Dagmar and snorted. "Five miles of golden spiderfloss, four of silver. And for a lure, the blue stained glass from the window of Epiphany. And everyone knows the Barbary Fish frequents the hills at Devil's End."

"You've never tried to catch him yourself?"

"I'm not mad."

"Well then, thank you, sir," said Dagmar.

That night, someone broke the Epiphany window. It was later determined that a stone had been thrown through it. Three days after this Dagmar's aunt found the family tapestry bundled up in the cupboard under the stairs. Half of it had been unravelled, and the gold and silver threads had all been pulled out. None of the servants would own up to doing it.

Shortly afterwards, Dagmar became suddenly attentive at her macramé and crochet lessons. Madam Loge began to entertain cautious hopes for her reform.

Ten days later, Dagmar appeared dripping wet at Eora's door. "You'll have to help me," said Dagmar. She led her friend to Leechfield where a gathering of fishermen were ringed around the convex, glittering side of an enormous fish.

"Is that the Barbary—?"

"Well, no actually," said Dagmar. "But it's quite a respectable one I think. It dragged me across Leechfield and all along the Sonorous River. Do you see this?" Dagmar proudly displayed a missing tooth. "Came out when I hit the Bridge. No one warned me it might take me up. Anyway, it dropped me in the sea and I suppose it expected me to let go, but I wasn't going to give it the satisfaction. I worried it about a bit, then it seemed to tire, enough that I could wind it in close enough to start biffing and kicking it. It got the message and went to ground here. Which was lucky, as I didn't fancy landing in the quarry."

"What are you going to do with it?" said Eora.

"Have it bronzed, of course. It's easily bigger than any of the ones in the tower now."

Eora's eyes grew wide, but she didn't comment. The look of fanatical determination in Dagmar's eyes stilled her tongue.

HENRY, AS IT happened, was neither pleased nor impressed when Dagmar, accompanied by a parade of dancing acrobats and men in military costume, presented the bronzed fish to him at the door of the tower.

"That won't fit up the steps," he said.

"We'll hoist it from outside," said Dagmar. "This is a gift to you, a token of my esteem."

"Look," said Henry. He glanced at the acrobats somersaulting crosswise in front of him and lowered his voice. "Stop doing this."

"Doing what?"

"Giving me things, publicly declaring your feelings for me."

"Martidel Bayliss didn't stop trying to catch the Barbary fish and look at him."

"Right, but he never caught it, though, did he?" said Henry.

"No, but he spent his entire life trying. Isn't that utterly marvelous? That is dedication, Henry, as I am dedicated in my love for you."

"But I don't love you. I don't even like you. What you're doing... It's embarrassing me. It's insulting. Stop it."

Dagmar's face fell, and her brow furrowed in thought. "Very well." She bowed. "But take the fish."

"SO, YOU HAVE seen sense at last," said Eora as they sipped wine in the conservatory.

Dagmar shrugged. "If you mean have I given up, then no. Not at all."

"But he ordered you to leave him alone."

"Ah, yes. And that is because I have not done enough to earn his love. I have not sacrificed enough, I have not suffered enough."

"And you think he has not suffered enough either." Eora sighed. "This is fatuous. It's senseless."

"No. Senseless is in the country of Giving Up. What is the purpose of living if I can't pursue him? If I stopped, it would mean I didn't really love him. And I do."

"He says he doesn't love you."

"If he really believes that..."

"Yes?" Eora leaned closer.

"...then I haven't been trying hard enough."

Exasperated, Eora proclaimed, "A woman pursuing a man is a scandal. I think you are doing it to mortify your Aunt Lydia."

"I am doing it for the glory," said Dagmar. "A glory most women are afraid to taste."

FOR A FEW WEEKS nothing new transpired, except that Dagmar began to pay rapt attention to her art instructor. Then one morning, a large mural was found covering the front of Dagmar's house. It depicted a man, endowed with yak-like proportions, strutting atop an enormous tower from which a golden fish hung.

The next day, Henry of the bell tower asked the swineherd's daughter to marry him.

"Now, even you must admit defeat," said Eora.

"Not at all," said Dagmar. "This girl, what do you know about her?"

"She's very beautiful."

"Ah," said Dagmar, "But did she earn her beauty, or did she happen upon it by way of the womb? What has she done to be worthy of Henry?"

"Well, nothing," said Eora, "except I suppose that he likes her. And perhaps she was patient enough to let him make up his own mind about that, and doesn't wake him at midnight singing his praises, or drop uninvited fish and acrobats in his lap."

"No," said Dagmar. "It can't be that simple. If he truly believes he loves her, then it's because I haven't tried hard enough."

EORA HAPPENED TO meet Henry in Evelyn Street the next afternoon. They greeted each other cordially, if cautiously, like two people who share an embarrassing complaint.

"It won't work," said Eora. "I mean, if that's why you've done it."

"What?"

"Proposing to another girl. In fact, I think you've spurred her on to try even harder to win you."

"Tell her from me that she can go to hell," Henry muttered. "Tell her I'll send her there myself if she doesn't stop it." He stalked off.

Eora went off to do as he asked, but at the door to Dagmar's house, she stopped. Her hand, lifted to tap on the door, dropped to her side, and she regarded it pensively. What was the use talking to Dagmar? She wouldn't listen to reason.

A FEW DAYS LATER, Dagmar was sitting on the bank of the Sonorous River, working out a plot to stop Henry's wedding.

She was planning the speech she would make when the minister asked if there were any objections to the wedding. Of course there were. Anyone could see that Henry had become engaged solely to annoy her and not because he loved this other girl.

Dagmar was deep in thought writing her speech when a shadow fell across the parchment. She looked up, but instead of an obtrusive cloud, she saw a man looming over her.

"You're in my light," said Dagmar. "Move off."

"You are my light," said the man.

Dagmar, whose head had bowed to the task of writing almost before the words were out of her mouth looked up suddenly. "What?"

"Lady for whose sake alone I breathe, listen while I tell you that I adore you."

It was the fisherman from Leechfield. The old, ragged man who'd told her about baiting hooks.

"You're cracked!" said Dagmar. "You're twice my age for a start. And anyway, in case you hadn't noticed, and you must be deaf, mad and stupid if you haven't, I'm in love with Henry the tower boy."

"Henry is engaged to the swineherd's daughter."

"That's what he thinks," said Dagmar, standing up and brushing the heads of grasses from her cloak.

"He is betrothed," said the fisherman. "Whereas I am not. We are better suited to each other." He began to follow Dagmar as she made her way back to the square.

"Don't you have fish to catch?" said Dagmar.

"None more beautiful than you, and none more sly and worthy than you." As they walked, the fisherman's voice rose so that people in the square turned to watch them.

"Look," said Dagmar, rounding on him, "Look here, back off. I've told you to go. Everyone knows where my heart belongs."

The fisherman fell to his knees. "Most glorious girl, listen to me while I declare my love for you in front of these people, for no one could be more worthy of a fisherman's love than the woman who tried for the Barbary Fish."

"Yes, yes, all right. Everyone knows I didn't get him, but thanks for bringing it to their attentio

n. Now clear off."

The fisherman grabbed hold of the hem of Dagmar's cloak so that she had to jerk it free. She turned and stalked off.

The fisherman followed her, tossing glass-glazed fish scales over her head. "A tribute," he said.

Someone nearby sniggered. Dagmar had to make an undignified run to her house, slamming and bolting the door behind her.

"IT ISN'T FUNNY, EORA," said Dagmar. She had to raise her voice to be heard over the wailing coming from below the window as the Leechfield fisherman serenaded her.

"I think it's romantic," said Eora. "Why don't you consider him?"

"Look, Eora, there are two kinds of people in the world. The Pursuers and the Pursued. And the Pursuers neither like nor wish to be pursued. It is an insult to their nature."

"I heard that Henry proposed to the swineherd's daughter," said Eora. "She didn't pursue him at all."

Dagmar frowned. "Do you know, that man is singing off-key. I didn't sing off-key when I serenaded Henry...did I?"

Eora shrugged. "I couldn't really tell over Henry's shouting at you to shut up."

"And at least I composed an original song," said Dagmar. "This raving nit is borrowing an old chestnut and trotting it out like it's the latest thing. He's doing a poor job of it all around." Dagmar shot to her feet and marched to the bathroom, filled a tub with the coldest water she could manage and wrestled it back to the window. She tipped the water out of the window onto the singing fisherman.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

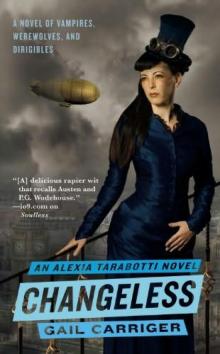

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

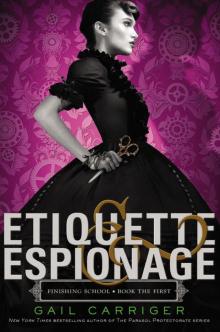

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

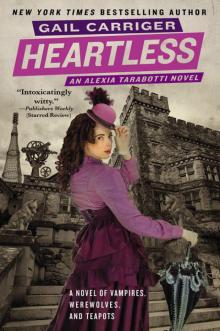

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

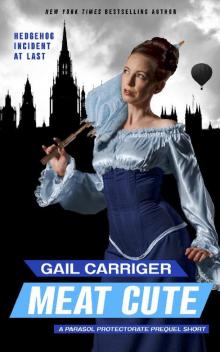

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3