- Home

- Gail Carriger

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Page 8

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Read online

Page 8

This was lost on Mrs. Tunstell, who said only, “Well, there you have it. Constructive occupation and attention to good works can have just such a beneficial effect on peevish young ladies. Either that or she has fallen in love.”

Alexia could hardly find the words to explain in a manner that Ivy would comprehend. “It is a feminine-advocacy association.”

Ivy gasped and clutched at her bosom. “Oh, Alexia, what a thing to say out loud!”

Lady Maccon realized that Ivy might be right—they were heading into highly indecorous, not to say dangerous, territory. “Well, of course”—Alexia cleared her throat ostentatiously—“do tell me, what business is it that has brought you to call this afternoon, my dear Ivy?”

“Oh, Alexia, I do have quite the surfeit of delightful news to relate. I hardly know where to start.”

“The beginning, I find, is usually the best place.”

“Oh, but, Alexia, that’s the most overwhelming part. It is all happening at once.”

Lady Maccon took a firm stance at this juncture—she rang for Floote. “Tea is obviously necessary.”

“Oh, my, yes,” agreed Ivy fervently.

Floote, having anticipated just such a request, came in with tea, treacle tart, and a bunch of grapes imported at prodigious expense from Portugal.

Lady Maccon poured the tea while Ivy waited, fairly vibrating with her news but unwilling to begin recitation until her friend had finished handling the hot liquid.

Alexia placed the teapot carefully back on the tray and handed Ivy her cup. “Well?”

“Have you noticed anything singular about my appearance?” Ivy immediately put the cup down without taking a sip.

Lady Maccon regarded her friend. If a brown dress could be called glaring, Ivy’s could be so described. It boasted an overdress and bustle of chocolate satin with a pure white skirt striped, like a circus tent, in the same shade. The accompanying hat was, of course, ridiculous: almost conical in shape but covered with what looked to be the feathers of at least three pheasants mixed in with a good deal of blue and yellow silk flowers. However, none of these extremes of dress were unusual for Mrs. Tunstell. “Not as such.”

Ivy blushed beet red, apparently mortified by what she must now relate given Alexia’s failed powers of observation. She lowered her voice. “I am very eager for the tea.” This garnered no response from the confused Alexia, as Ivy wasn’t drinking it. So Ivy soldiered bravely on. “I am—oh, dear, how to put this delicately?—anticipating a familial increase.”

“Why, Ivy, I didn’t know you expected any kind of inheritance.”

“Oh, no.” Ivy’s blush deepened. “Not that kind of increase.” She nodded significantly toward Alexia’s portly form.

“Ivy! You are pregnant!”

“Oh, Alexia, really, must you say it so loudly?”

“Felicitations, indeed. How delightful.”

Ivy moved the conversation hurriedly onward. “And Tunny and I have decided to form our own dramatic association.”

Lady Maccon paused to reinterpret this confession. “Ivy, are you saying you intend to establish an acting troupe?”

Mrs. Tunstell nodded, her curls bouncing. “Tunny thinks it a good plan to start a new family of players as well as a new family, as he is keen on saying.”

A family, indeed, Alexia thought. Having left the werewolf pack, Tunstell must be trying, in his own way, to build a new pack for himself. “Well,” she said, “I do wish you all the best luck in the world. However, Ivy—and I do not mean to be crude—how have you managed to gather the means to fund such an undertaking?”

Ivy blushed and lowered her eyes. “I was dispatched to consult you on just such a subject. I understand Woolsey is quite enthusiastic in its patronage of artistic endeavors. Tunny implied you even had some capital invested in a circus!”

“Indeed, but, Ivy, for obvious reasons, those are in the interest of furthering the pack. Claviger recruitment and so forth. Tunstell has voluntarily severed any such connection.”

Ivy nodded glumly. “I thought you would say as much.”

“Now, wait just a moment. I’m not so feeble a friend as to abandon anyone, especially you, my dear, when in need.” Lady Maccon frowned in thought. “Perhaps I could dip into my own coffers. You may not be aware, but my father left me rather well set up, and Conall is quite generous with a weekly allowance. We have never discussed my personal income, but he seems disinterested in my financial affairs. I am convinced he shouldn’t object if I were to become a patron of the arts. Why should Woolsey have all the fun?”

“Oh, Alexia, really? I couldn’t ask such a thing of you!” protested Ivy in a tone that suggested this had been her objective in calling all along.

“No, no.” Alexia was becoming rather entranced with the proposal. “I think it a capital idea. I wonder if I might ask a rather odd favor in return?”

Ivy looked amenable to anything that might further her husband’s goal. “Oh, please do.”

Alexia grappled with how exactly to phrase this next question without exposing too much of her nature to her dear friend. She had never told Ivy of her preternatural state, nor of her post as muhjah and the general investigative endeavors that resulted.

“I find myself curious as to the activities of the lower orders. No insult intended, my dear Ivy, but even as the mistress of your own troupe, and clientele notwithstanding, you will have a certain amount of contact with less savory elements of London society. I would appreciate . . . information . . . with regards to these elements on occasion.”

Mrs. Tunstell was overcome with such joy upon hearing this that she was moved to dab at one eye with an embroidered handkerchief. “Why, Alexia, my dear, have you undertaken an interest in scandal mongering at last? Oh, it is too much. Too wonderful.”

Even prior to her marriage, Miss Ivy Hisselpenny’s social position had prevented her from attending events of high standing, while Miss Alexia Tarabotti had suffered under the yoke of just such events. As far as Ivy was concerned, this yielded up a poor quality and quantity of gossip. The Alexia of her girlhood had not been curious about the interpersonal relationships of others, let alone their dress and manners.

The handkerchief lowered and Ivy’s face became suffused with a naive cunning. “Is there anything in particular you wish me to look out for?”

“Why, Ivy!”

Mrs. Tunstell sipped her tea coquettishly.

Lady Maccon took the plunge. “As a matter of fact, there have been rumors of late with regards to a threat upon a certain peer of the realm. I cannot say more, but if you wouldn’t mind?”

“Well, I did hear Lord Blingchester’s carriage was to be decommissioned.”

“No, Ivy, not that kind of threat.”

“And the Duchess of Snodgrove’s chambermaid was so incensed recently that she indicated she might actually not affix her hat properly for the midsummer ball.”

“No, not quite that either. But this is all intriguing information. I should appreciate your continued conversation and company even after your evolved circumstances.”

Ivy closed her eyes and took a small breath. “Oh, Alexia, how kind of you. I did fear . . .” She flipped open a fan and fluttered it in an excess of sentimental feeling. “I did fear that once Tunny and I launched this endeavor, you would be unwilling to continue the association. After all, I intend to perhaps take on some small roles myself. Tunny thinks I may have dramatic talent. Being seen to take tea with the wife of an actor is one thing, but taking tea with the actress herself is quite another.”

Lady Maccon shifted forward as much as possible and stretched out a hand to rest softly atop Mrs. Tunstell’s. “Ivy, I would never even consider it. Let us say no more on the subject.”

Ivy seemed to feel the time had come to move on to yet another pertinent bit of news. “I did have one other thing to relate to you, my dear Alexia. As you may have surmised, I have had to give over my position as assistant to Madame Lefo

ux. Of course, I shall miss the society of all those lovely hats, but I was there just the other evening when a very peculiar event occurred. Given your husband’s state, I immediately thought of you.”

“How very perspicacious.” Much to her own amazement, Lady Maccon had found that Mrs. Tunstell, a lady of little society and less apparent sense, often had the most surprising things to relate. Knowing well that the best encouragement was to say nothing, Alexia drank her tea and gave Ivy a dark-eyed look of interest.

“Well, you should never believe it, but I ran into a scepter in the street.”

“A scepter . . . what, like the queen’s?”

“Oh, no, you know what I mean. A ghost. Me, can you imagine? Right through it I went, all la-di-da. I could hardly countenance it. I was completely unnerved. After I had recovered my capacities, I realized the poor thing was a tad absent of good sense. Subsequent to much inane burbling, she did manage to articulate some information. She seemed peculiarly attracted to my parasol, which I was carrying at night only because my business with Madame Lefoux had taken longer than expected. Otherwise, you understand, I have always found your habit of toting daytime accessories at all hours highly esoteric. Never mind that. This ghost seemed peculiarly interested in my parasol. Kept asking about it. Wanted to know if it did anything, apart from shield me from the sun, of course. I informed her flat out that the only person I knew who boasted a parasol that extruded things was my dear friend Lady Maccon. You remember I saw yours emit when we were traveling in the north? Well, I told this to the ghost in no unceremonious terms, at which point she got most stimulated and asked as to your current whereabouts. Well, since she was a ghost and, as such, tethered within a shortened area of the location, I saw no reason not to relay your new address to her. It was all very odd. And she kept repeating the most peculiar turn of phrase, regarding a cephalopod.”

“Oh, indeed? What exactly did she say, Ivy?”

“ ‘The octopus is inequitable,’ or some such drivel.” Ivy looked as though she might continue her discussion, except at that moment she caught sight of Felicity through the open parlor door.

“Alexia, your sister appears to be most unbalanced. I am quite convinced I just observed her wearing a lemon-yellow knit shawl. With a fringe. Going out into public. I cannot countenance it.”

Lady Maccon closed her eyes and shook her head. “Never mind that now, Ivy.”

“Convinced, I tell you. How remarkable.”

“Anything more about the ghost, Ivy?”

“I think it might have had something to do with the OBO.”

This comment brought Alexia up short. “What did you just say?”

“The Order of the Brass Octopus—you must have heard of it.”

Lady Maccon blinked in shock and put her hand to her stomach where the infant-inconvenience kicked out in surprise as well. “Of course I have heard of it, Ivy. The question is, how have you?”

“Oh, Alexia, I have been working for Madame Lefoux for positively ages. She has been traveling overmuch of late, and her appearance can be very distracting, but I am not so unobservant as all that. I am well aware that when she is in town, she undertakes fewer hat-orientated activities than hat-focused ones. She runs an underground contrivance chamber as I understand it.”

“She told you?”

“Not exactly. If Madame Lefoux prefers to keep things a secret, who am I to gainsay her? But I did look inside some of those hatboxes of hers, and they do not always contain hats. I did inquire as to the specifics, and Madame Lefoux assured me it was better if I not become involved. However, Alexia, I wouldn’t want you to think me ignorant. Tunny and I do talk about such things, and I have eyes enough in my head to observe, even if I do not always understand.”

“I apologize for doubting you, Ivy.”

Ivy looked wistful. “Perhaps one day you, too, will take me into your confidence.”

“Oh, Ivy, I—”

Ivy held up a hand. “When you are quite ready, of course.”

Alexia sighed. “Speaking of which, you must excuse me. This news about the ghost, it is of no little importance. I must consult my husband’s Beta immediately.”

Ivy looked about. “But it is daylight.”

“Sometimes even werewolves are awake during the day. When the situation demands it. Conall is asleep, so Professor Lyall is probably awake and at his duties.”

“Is a cephalopod so dire as all that?”

“I am afraid it might be. If you would excuse me, Ivy?”

“Of course.”

“I shall inform Floote about the little matter of my patronage. He will set you up right and proper with the necessary pecuniary advance.”

Ivy grabbed at Lady Maccon’s hand as she passed. “Oh, thank you, Alexia.”

Alexia was as good as her word, going immediately to Floote and issuing him with instructions. Then, in the interest of economy and perhaps saving herself a trip to BUR, she casually asked, “Is there a local OBO chapter in this area? I understand it is quite the secret society but thought perhaps you might know.”

Floote gave her a meditative look. “Yes, madam, a block over. I noticed the marking just after you began visiting with Lord Akeldama.”

“Marking, Floote?”

“Yes, madam. There is a brass octopus on the door handle. Number eighty-eight.”

CHAPTER FIVE

The Lair of the Octopus

Number 88 was not a very impressive domicile. In fact, it was one of the least elegant in the neighborhood. While its immediate neighbors were nothing when compared to Lord Akeldama’s abode, they still put their very best brick forward. They acknowledged, in an entirely unspoken way, that they were denizens of the most fashionable residential area in London and that architecture and grounds should earn this accolade. Number eighty-eight was altogether shabby by comparison. Its paint was not exactly peeling, but it was faded, and its garden was overgrown with herbs gone to seed and lettuces that had bolted.

Scientists, thought Alexia as she made her way up the front steps and pulled the bell rope. She wore her worst dress, altered to compensate for her stomach and made of a worsted fabric somewhere between dishwater brown and green. She couldn’t remember why she’d originally purchased the poor sad thing—probably to upset her mother. She had even borrowed one of Felicity’s ugly shawls, despite the fact that the day was too warm for such a conceit. With the addition of a full white mob cap and a very humble expression, she looked every inch the housekeeper she wished to portray.

The butler who answered her knock seemed to feel the same, for he did not even question her status. His demeanor was one of pedantic pleasantness, exacerbated by a round jolliness customarily encountered among bakers or butchers not butlers. He sported a stout neck and a head of wildly bushy white hair that called to mind nothing so much as a cauliflower.

“Good afternoon,” said Alexia, bobbing a curtsy. “I heard your establishment was in need of new staff, and I have come to inquire about the position.”

The butler looked her up and down, pursing his lips. “We did lose our cook several weeks ago. We have been doing fine with a temporary, and we certainly don’t wish to take on someone in your condition. You can understand that.” It was said kindly, but most firmly, and meant to discourage.

Alexia stiffened her spine. “Oh, yes, sir. My lying-in shouldn’t be a day over a fortnight, and I do make the best calf’s-feet jelly you will ever taste.” Alexia took a gamble with that. The butler looked like the kind of man who liked jelly, his shape being of the jelly inclination already.

She was right. His squinty eyes lit with pleasure. “Oh, well, if that is the case. Have you references?”

“The very best, from Lady Maccon herself, sir.”

“Indeed? How comprehensive is your knowledge of herbs and spices? Our gentlemen residents, you understand, are mostly bachelors. Their table requirements are simple, but their extracurricular requests can be a tad esoteric.”

Alex

ia pretended shock.

The butler made haste to correct any miscommunication. “Oh, no, no, nothing like that. They simply may ask for quantities of dried herbs for their experiments. They are all men of intellect.”

“Ah. As to that, my knowledge is unequaled by any I have ever met before or since.” Alexia was rather enjoying bragging about things about which she knew absolutely nothing.

“I should find that very hard to believe. Our previous cook was a renowned expert in the medicinal arts. However, do come in, Mrs. . . . ?”

Alexia scrabbled for a name, then came up with the best she could at short notice. “Floote. Mrs. Floote.”

This butler didn’t seem to know her butler, for his expression did not alter at the improbability of such a pairing as Floote and Alexia. He merely ushered her inside and led her down and into the kitchen.

It was like no kitchen Alexia had ever seen. Not that she had spent much time in kitchens, but she felt she was at least familiar with the general expectations of such a utilitarian room. This one was pristinely clean and boasted not only the requisite number of pots and pans, but also steam devices, one or two massive measuring buckets, and what looked like glass jars filled with specimen samples lining the counters. It resembled the combination of a bottling factory, a brewery, and Madame Lefoux’s contrivance chamber.

Alexia made no attempt to disguise her astonishment—any normal housekeeper would be as surprised as she upon seeing such a strange cooking arena. “My goodness, what a peculiar arrangement of furnishings and utensils.”

They were alone in the kitchen, and it was just that time of the afternoon when most household staff had a brief moment to satisfy their own concerns before the tea was called for.

“Ah, yes, our previous cook had some interest in other endeavors apart from meal preparation. She was a kind of intellectual herself, if you would allow such a thing in a female. My employers sometimes encourage aberrant behavior.”

Alexia, having spent a goodly number of years immersed in books and having attended many Royal Society presentations, not to mention her intimacy with Madame Lefoux, could indeed allow such things in females, but in her current guise forbore to say so. Instead, she looked around in silence. Only to notice a prevalence of octopuses. They were positively everywhere, stamped onto jar lids and labels, etched into the handles of iron skillets, engraved onto the sides of copper pots, and even pressed into the top of a vat of soap set out to harden on a sideboard.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

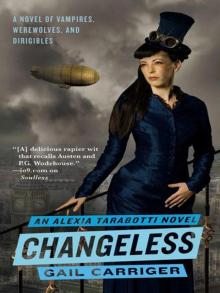

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

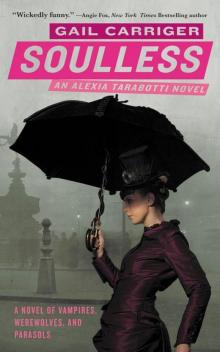

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

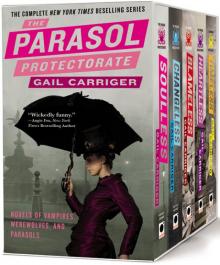

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

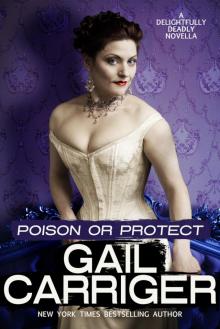

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

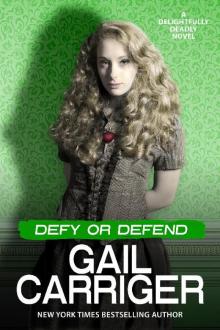

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3