- Home

- Gail Carriger

Blameless pp-3 Page 9

Blameless pp-3 Read online

Page 9

Alexia gave Madame Lefoux a sharp stare. They had not discussed revealing the personal details of her embarrassing condition to a French clockmaker!

“I must sit down.” Monsieur Trouvé groped without looking for a nearby chair and collapsed into it. He took a deep breath and then examined Alexia with even more interest. She wondered if he might try to wear the glassicals as well as the spectacles and the monocle.

“You are certain?”

Alexia bristled. She was so very tired of having her word questioned. “I assure you. I am quite certain.”

“Amazing,” said the clockmaker, seeming to recover some of his equanimity. “No offense meant, no offense. You are, you must realize, a marvel of the modern age.” The monocle went back up. “Though, not so very much like your dear father.”

Alexia glanced tentatively at Floote and then asked Monsieur Trouvé, “Is there anyone who did not know my father?”

“Oh, most people didn’t. He preferred things that way. But he dabbled in my circle, or I should say, my father’s circle. I met him only the once, and I was six at the time. I remember it well, however.” The clockmaker smiled again. “He did have quite the habit of making an impression, your father, I must say.”

Alexia was unsure as to whether this comment had an underlying unsavory meaning or not. Then she realized it must. Given what little she knew of her father, a better question might be, to which form of unsavory meaning was the Frenchman alluding? Still, she was positively dying of curiosity. “Circle?”

“The Order.”

“My father was an inventor?” That surprised Alexia. She had never heard that about Alessandro Tarabotti. All his journal entries indicated he was more a destroyer than a creator. Besides, by all accounts, preternaturals couldn’t really invent anything. They lacked the necessary imagination and soul.

“Oh, no, no.” Monsieur Trouvé brushed two fingers through his beard thoughtfully. “More of an irregular customer. He always had the oddest requests. I remember, once, my uncle talking about how he actually asked for a—” The clockmaker looked up at the doorway, apparently noticing something that made him stop. “Ah, yes, never mind.”

Alexia glanced over to see what had caused this gregarious fellow to silence himself. But there was nothing there, only Floote, impassive as always, hands laced behind his back.

Alexia looked to Madame Lefoux in mute appeal.

The Frenchwoman was no help. Instead, she excused herself from the discussion. “Cousin, perhaps I could go find Cansuse for some tea?”

“Tea?” Monsieur Trouvé looked taken aback. “Well, if you must. Seems to me you have been in England too long, my dearest Genevieve. I should think such an occasion as this would require wine. Or perhaps brandy.” He turned to Alexia. “Should I get out the brandy? You look as though you might need a bit of a pick-me-up, my dear.”

“Oh, no, thank you. Tea would be perfectly suitable.” In truth, Alexia thought tea a brilliant idea. It had taken well over an hour to conduct their train subterfuge, and while she knew it was worth it, her stomach objected on principle. Ever since the onset of the infant-inconvenience, food was becoming an ever more pressing concern in some form or another. She had always pondered food overmuch for the safety of her waistline, but these days a good deal more of her attention was occupied with where it was, how soon she could get it, and, on the more embarrassing occasions, whether it would remain eaten or not. Yet another thing to blame on Conall. Who would have thought that anything could affect my eating habits?

Madame Lefoux vanished from the room. There was an awkward pause while the clockmaker continued to stare at Alexia.

“So,” Alexia began tentatively, “through which side of the family are you related to Genevieve?”

“Oh, we aren’t actually family. She and I went to school together—École des Arts et Métiers. You’ve heard of it? Of course you have. Naturally, at the time, she was a he—always did prefer to play the man, our Genevieve.” There was a pause while bushy eyebrows descended in thought. “Aha, that is what is different! She is wearing that ridiculous fake mustache again. It has been a long time. You must be traveling incognito. What fun!”

Alexia looked mildly panicked, unsure as to whether she should tell this affable man about danger of a vampiric persuasion heading in their direction.

“Not to worry, I wouldn’t dare to pry. Regardless, I taught Genevieve everything she knows about clockwork mechanisms. And mustache maintenance, come to think on it. And a few other things of note.” The clockmaker stroked his own impressive mustache with forefinger and thumb.

Alexia didn’t quite follow his meaning. She was saved from having to continue the conversation by the return of Madame Lefoux.

“Where is your wife?” the Frenchwoman demanded of their host.

“Ah, yes, about that. Hortense slightly, well, died last year.”

“Oh.” Madame Lefoux did not look particularly upset by this news, only surprised. “I am sorry.”

The clockmaker gave a small shrug. “Hortense never was one for making a fuss. She caught a tiny cold down the Riviera way, and the next thing I knew, she had just given up and expired.”

Alexia wasn’t sure what to think of such a blasé attitude.

“She was a bit of a turnip, my wife.”

Alexia decided to be mildly amused by his lack of sentiment. “How do you mean, turnip?”

The clockmaker smiled again. Clearly, he had been hoping for that question. “Bland, good as a side dish, but really only palatable when there is nothing better available.”

“Gustave, really!” Madame Lefoux pretended shock.

“But enough about me. Tell me more about yourself, Madame Tarabotti.” Monsieur Trouvé scooted toward her.

“What more should you like to know?” Alexia wanted to ask him more questions about her father but felt that the opportunity had passed.

“Do you function the same as a male soulless? Your ability to negate the supernatural, is it similar?”

“Having never met any other living preternaturals, I always assumed so.”

“So, you would say, physical touch or very near proximity with a rapid reaction time on the part of the victim?”

Alexia didn’t like the word “victim,” but his description of her abilities was accurate enough, so she nodded. “Do you make a study of us, then, Monsieur Trouvé?” Perhaps he could help with her pregnancy predicament.

The man shook his head, his eyes crinkling up at the edges in amusement. Alexia was finding she did not mind the copious facial hair, because so much of the clockmaker’s expressions were centered in his eyes. “Oh, no, no. Far outside of my sphere of particular interest.”

Madame Lefoux gave her old school chum an assessing look. “No, Gustave, you never have been one for the aetheric sciences—not enough gadgetry.”

“I’m an aetheric science?” Alexia was mystified. In her experience as a bluestocking, such studies focused on the niceties of aetheronautics and supra-oxygenic travel, not preternaturals.

A diminutive maid with a shy demeanor brought in the tea, or what Alexia supposed passed for tea in France. The maid was accompanied by a low tray of foodstuffs on wheels, which seemed to be somehow trailing her about the apartments. It made a familiar tinny skittering noise as it moved. When the maid bent to lift the tray up and place it on a table, Alexia emitted an involuntary squeak of alarm. Quite unaware of her own athletic abilities until that moment, she jumped over and behind the couch.

Acting the part of footman in tonight’s French farce, she thought with a bubble of panicked hilarity, we have a homicidal mechanical ladybug.

“Good lord, Madame Tarabotti, are you quite well?”

“Ladybug!” Alexia managed to squawk.

“Ah, yes, a prototype for a recent order.”

“You mean, it is not trying to kill me?”

“Madame Tarabotti, I assure you, in my own home, I should never be so uncouth as to kill someone with a ladybug.�

��

Alexia came cautiously back out from behind the couch and watched warily as the large mechanical beetle, all unconcerned for her palpitating heart, trundled after the maid and back out into the hall.

“Your artisanship, I take it?”

“Indeed.” The Frenchman looked proudly after the retreating bug.

“I have encountered it before.”

Madame Lefoux turned accusing eyes onto Monsieur Trouvé. “Cousin, I thought you preferred not to design weapons!”

“I do! And I must say I resent the implication.”

“Well, the vampires have turned them into such,” Alexia said. “I experienced a whole herd of homicidal ladybugs, sent to poke me in a carriage. Those very antennae that yours was using to carry the tea tray had been replaced with syringes.”

“And one exploded when I went to examine it,” added Madame Lefoux.

“How perfectly dreadful.” The clockmaker frowned. “Ingenious, of course, but not my modifications, I assure you. I must apologize to you, dear lady. These things always seem to happen when dealing with vampires. Although it is hard to refuse such consistent customers with such prompt accounting.”

“Can you reveal the name of your client, cousin?”

The clockmaker frowned. “American gentleman. A Mr. Beauregard. Ever heard of him?”

“Sounds like a pseudonym,” said Alexia.

Madame Lefoux nodded. “It is rather common to use handlers in this part of the world, I’m afraid. The trail will have gone quite cold by now.”

Alexia sighed regretfully. “Ah, well, deadly ladybugs will happen, Monsieur Trouvé. I understand. You can repair my finer feelings with some tea, perhaps?”

“Of course, Madame Tarabotti. Of course.”

To be certain there was tea, of indifferent quality, but Alexia’s attention was drawn to the food on offer. There were stacks of raw vegetables—raw!—and some sort of pressed gelatinous meat with tiny nutty-looking digestive biscuits. There was nothing sweet at all. Alexia was deeply suspicious of the whole arrangement. However, upon selection of a small mound of nibbles, she found the fare to be more than passing delicious, with the exception of the tea, which proved itself to be as indifferent in taste as it had appeared initially.

The clockmaker nibbled delicately at some of the foodstuffs but took no libations, commenting that he believed tea would make a superior beverage served cold over ice. Were ice, of course, to become a less expensive commodity. At which statement, Alexia utterly despaired of both him and his moral integrity.

He continued his conversation with Madame Lefoux, as though they had never been interrupted. “On the contrary, my dear Genevieve, I am interested enough in the aetheric phenomena to keep up with the current literature out of Italy. Contrary to the British and the American theories on volatile moral natures, blood derangements, and feverish humors, the Italian investigative societies now hold that souls are connected to the correct dermatological processing of ambient aether.”

“Oh, for goodness’ sake, how preposterous.” Alexia was not impressed. The infant-inconvenience appeared to feel equally unimpressed by raw vegetables. Alexia stopped eating and put a hand to her stomach. Damn and blast the annoying thing. Couldn’t it leave her in peace for one meal?

Floote, previously occupied with his own comestibles, immediately moved toward her in concern.

Alexia shook her head at him.

“Ah, you are a reader of scientific literature, Madame Tarabotti?”

Alexia inclined her head.

“Well it may seem absurd to you, but I believe their ideas have merit. Not the least of which being the fact that this particular theory has temporarily halted Templar-sanctioned vivisections of supernatural test subjects.”

“You are a progressive?” Alexia was surprised.

“I try to stay out of politics. However, England seems to be doing rather well having openly accepted the supernatural. That is not to say I approve. Making them hide, however, has its disadvantages. I should love to have access to some of the vampires’ scientific investigations for one; the things they know about clocks! I also do not believe the supernatural should be hunted down and treated like animals as in the Italian mode.”

The little room in which they sat turned a pretty shade of gold as the sun began to set over the Parisian rooftops.

The clockmaker paused upon noticing the change. “Well, well, we have chatted long enough, I suspect. You must be exhausted. You will be staying the night with me, of course?”

“If you don’t mind the imposition, cousin.”

“It’s no trouble at all. So long as you forgive the arrangements, for they will be quite cramped. I am afraid you ladies will have to bunk down together.”

Alexia gave Madame Lefoux an assessing look. The Frenchwoman had made her preferences, and her interest, clear. “I suspect my virtue is safe.”

Floote looked as though he would like to object.

Alexia gave him a funny look. There was no possible way her father’s ex-valet could be a prude in matters of the flesh. Was there? Floote had terribly rigid ideas about sensible dress and public behavior, but he had never batted a single eye at the entirely untoward private doings of Woolsey Castle’s rambunctious werewolf pack. On the other hand, he had never particularly liked Lord Akeldama, either. Alexia twitched a small frown in his direction.

Floote gave her a blank stare.

Perhaps he still mistrusted Madame Lefoux for some other reason?

Since puzzling over the matter would certainly yield no results, and talking to Floote—or, more precisely, at Floote—never did any good, Alexia swept by him and followed Monsieur Trouvé up the hallway to a tiny bedroom.

Alexia had changed into a claret-colored taffeta visiting dress and was just enjoying a little nap before supper when the most amazing racket awakened her. It seemed to be emanating from the downstairs clock shop.

“Oh, for the love of treacle, what now?”

Grabbing her parasol in one hand and her dispatch case in the other, she charged out into the hallway. It was very dark, as the lights in the apartment were not yet lit. A warm glow emanated up from the shop below.

Alexia bumped into Floote at the top of the stairs.

“Madame Lefoux and Monsieur Trouvé have been consulting on matters clock-related while you rested,” he informed her softly.

“That cannot possibly account for such a hullabaloo.”

Something crashed into the front door. Unlike London, the Paris shops did not stay open late in order to cater to werewolves and vampires. They shut down before sunset, locked firmly against any possible supernatural clientele.

Alexia and Floote bounded down the stairs—as much as a dignified butler-type personage and a pregnant woman of substance can be said to bound. There Alexia thought Paris’s closed-door policy might well have its merits. For just as she entered the clock shop, four large vampires did the same by way of the now-broken front door. Their fangs were extended, and they did not look in favor of formal introductions.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Trouble with Vampires

The trouble with vampires, thought Professor Lyall as he cleaned his glassicals with a handkerchief, was that they got hung up on the details. Vampires liked to manipulate things, but when things did not turn out as planned, they lost all capacity for refinement in the resulting chaos. The upshot was that they panicked and resorted to a course of action that never ended as elegantly as they had originally hoped.

“Where is our illustrious Alpha?” asked Hemming, sitting down at the table and helping himself to several slices of ham and a kipper. It was dinnertime for most, but for the werewolves this was breakfast. And since gentlemen were never served at breakfast, the staff merely provided mounds of meat and let the pack and clavigers see to themselves.

“He is in the clink and has been all day, sobering up. He was so drunk last night he went wolf. The dungeon seemed like the best place to stash him.”

&nbs

p; “Golly.”

“Women will do that to a soul. Best avoided, if you ask me.” Adelphus Bluebutton wandered in, followed shortly thereafter by Rafe and Phelan, two of the younger pack members.

Ulric, silently chomping on a chop at the other end of the table, glanced up. “No one did ask you. No one has ever been in any doubt as to your preferences.”

“Some of us are less narrow-minded than others.”

“More opportunistic, you mean to say.”

“I get bored easily.”

Everyone was grumpy—it was that time of the month.

Professor Lyall, with great deliberation, finished cleaning his glassicals and put them on. He looked around at the pack through the magnified lens. “Gentlemen, might I suggest that a discussion of preference is better suited to your club? It is certainly not the reason I have called a meeting this evening.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You will note that the clavigers have not been invited?”

Around him, all the immortal gentlemen nodded. They knew that this meant Lyall wanted to discuss a serious matter with the pack alone. Normally, the clavigers were in on everyone’s business. Living with several dozen mostly out-of-work actors will do that to a man’s private life—that is, make it considerably less private.

All the werewolves seated about the large dining table tilted their heads so that their necks were exposed to the Beta.

Professor Lyall, aware that he now had their full attention, began the meeting. “Given that our Alpha is pursuing a new and glorious career as an imbecilic twit, we must prepare for the worst. I require two of you to take leave of your military duties to help handle the extra BUR workload.”

No one questioned Professor Lyall’s right to make changes to the status quo. At one point or another, each member of the Woolsey Pack had tested himself against Randolph Lyall. All had discovered the damage inherent in such an undertaking. They had, as a result, settled into the realization that a good Beta was as valuable as a good Alpha, and it was best to be happy that they had both. Except, of course, that now their Alpha had gone quite decidedly off the rails. And their reputation and position as England’s premier pack was one that had to be defended constantly.

Romancing the Werewolf

Romancing the Werewolf Romancing the Inventor

Romancing the Inventor Manners & Mutiny

Manners & Mutiny Competence

Competence Waistcoats & Weaponry

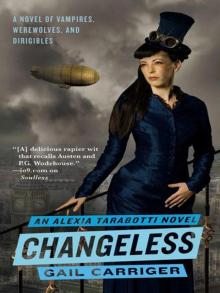

Waistcoats & Weaponry Changeless

Changeless Blameless

Blameless Soulless

Soulless Curtsies & Conspiracies

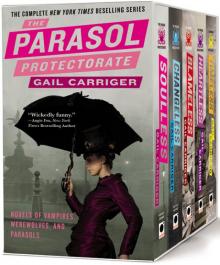

Curtsies & Conspiracies The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set

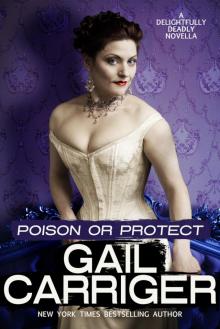

The Parasol Protectorate Boxed Set D2D_Poison or Protect

D2D_Poison or Protect Funny Fantasy

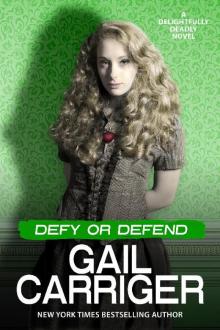

Funny Fantasy Defy or Defend

Defy or Defend Imprudence

Imprudence Reticence

Reticence Etiquette & Espionage

Etiquette & Espionage Heartless

Heartless Prudence

Prudence Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless

Parasol Protectorate 01 - Soulless Fairy Debt

Fairy Debt My Sister's Song

My Sister's Song Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second

Changeless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Second Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First

Soulless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the First Soulless pp-1

Soulless pp-1 Changeless pp-2

Changeless pp-2 Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth

Heartless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Fourth Meat Cute

Meat Cute Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School)

Etiquette & Espionage (Finishing School) How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1)

How To Marry A Werewolf (Claw & Courtship Novella Book 1) Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third

Blameless: The Parasol Protectorate: Book the Third Heartless pp-4

Heartless pp-4 Etiquette & Espionage fs-1

Etiquette & Espionage fs-1 Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella

Romancing the Inventor: A Supernatural Society Novella Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2

Curtsies & Conspiracies fs-2 The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6)

The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn't, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar (The Parasol Protectorate Book 6) Blameless pp-3

Blameless pp-3